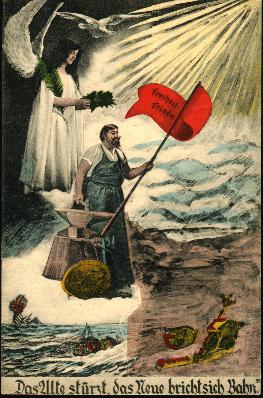

The old collapses, the new arises

credit: Propaganda Posters of the Great War

As the First World War progressed, the Kaiserreich’s ambitions for German military domination of Europe became clearer and clearer: the fate of Europe was to become satellite states of a highly militarised Germany, a strategic goal known as Mitteleuropa.

Rather than causing the SPD leadership to recoil from their close co-operation with the government as this sober reality was unveiled, they became more rabid in their defense of Germany’s alleged historical mission.

It was in this context that Kautsky engaged in a series of polemics with socialist supporters of the burgfrieden, as the co-operation between the socialists and the government was called.

One such pamphlet is Die Vereinigten Staaten Mitteleuropas (pdf), to date untranslated into English. We present below a translation by Noa Rodman of its concluding three pages.

The pamphlet was written in late 1915 and published early the following year. The section below warns that revolution is coming to Europe and that the Czarist government will be the first to fall. The impetus to civil peace that is common at the outbreak of war due to the population’s fear about the potential consequences of defeat by an external power, cannot last forever and especially not the end of the war.

Thus, the class struggle which was temporarily suppressed was sure to break out once again. But the prognosis is not all rosy as a revolution arising out of war, particularly such a massive conflagration as WWI, is not an easy place from which to build a socialist mode of production.

————————————————————————————————————————

Die Vereinigten Staaten Mitteleuropas

Neither I nor Bebel ever expected the outbreak of war to bring revolution. Both of us thought to keep the party away from any obligation to undertake revolutionary action at the outbreak of the war, because of our conviction that such an obligation could not be fulfilled.

Already in June 1907, before the Stuttgart International Congress, I developed this thought in a preface to my brochure Patriotismus und Sozialdemokratie, where I showed that we, as long as we lack the strength to take political power during peace, would also be unable to prevent war. The attempts to do were certain to meet defeat.The viewpoint does not have to discourage us, if we only stay loyal to our oppositional fundamentals. Then in the course of the war the confidence of the masses in us must rise:

The longer the war lasts, the more the masses will listen to us, the more our political standing and our political might will increase. Then, at the end of the war, we can count on great success.

Governments are never stronger than at the outbreak of war, and I can’t recall any example in history where a declaration of war was met by an insurrection in its own land. Even the bankrupt French Empire in 1870 and the likewise Czarist Empire in 1904 met with no resistance at the opening of their wars.

On the other hand, there have been no great wars in Europe in the last 100 years whose end did not, in one way or another, bring deep change of the political system in its wake. Insofar as that was not so much due to the direct military results of war but due to its unintended consequences, one can mark every European wars for the last century as the locomotive of world history. Indeed, this locomotive travels fastest when the direct results of war are smallest and stand out of all proportion to the sacrifices made.

When the danger that threatens the country from the outside recedes, when the a situation of peace is recovered, and when the pressure of an external enemy is gone, then the internal battle lights up with all the more energy. And the more any critical voices were suppressed during the war, the more the opposition was locked in, the higher the critical energy is pent up.

Russia, whose government before the war even then found itself in an unstable equilibrium, which has suffered the greatest military defeats and which most closely stifles any internal dissent, will be the one that suffers this first.

We cannot yet know which forms the impending collapse of Czarism will take. The only thing one can reveal with any certainty about the forms of a coming revolution is that it will look different than its predecessor. That must be so, since every revolution removes the social and political conditions through which it was generated and thereby makes it impossible that the next one resembles it, as the following one is engendered from altered conditions.

Even so, both revolutionaries and reactionaries still portray a coming revolution on the model of the past and accordingly set their tactics rather than taking into account this new situation.

Admittedly one can learn from experience, but the experiences of past revolutions are only part of the complex of facts of experiences, from which we have to learn. We must always try to lay the experience of the whole of the previous social development and the present situation of society as the basis of our action. As no mortal is given to create this “universal cohesion”, it is is impossible to speak with definiteness about the coming forms of change in the political system.

It is therefore impossible to know today which forms the coming collapse of Czarism will take. It is only certain that it will look different than the one of 1905. And it is to be expected that it will move the whole of Europe even deeper than the latter. Back then it sufficed to make all national differences and oppositions vanish. These, which today are so profound, so self-evident, so inextinguishable, were in 1905 completely done away with; the whole of Europe was divided into two international camps, one conservative and one revolutionary. The effects on Russia’s neighbouring countries, namely Austria and the Balkan states, were enormous.

Comrades Pernerstorses and Leuthner not only declare war on the Russian government, but also on the Russian people and want to cut it off from Europe and exile it to Asia, since it only brings harm to Western culture. And yet Austria’s biggest advance, the last electoral reform, was won through the pressure of the Russian revolution (1905). Without the uprising of the Russian people the grim denouncers of Russian “People’s Imperialism” would hardly have arrived at their present parliamentary mandates.

Russia is today no longer merely the country of despotism against which Marx and Engels in the past demanded war, but the country of revolution.

If we cannot yet know which forms the coming revolt of the Russian people will take, it cannot be doubted that it will provoke powerful repercussions in Western Europe. And that it must be far more potent than it was one decade ago.

However the war may turn out, it is certain that it will leave Europe in the deepest misery. The production process will be in deepest disruption, lacking capital for the run of production as much as the indispensable proportionality for individual branches of production.

Inflation and unemployment will besiege the proletarian masses, which will greatly swell through the destruction of countless small businesses in commerce and industry. At the same time the emergency will take political expression in new taxes, which will be double or treble the last ones. Their jolting political effect is increased hugely when the peace brings a new era of arms races, whose costs, based on the experience of this war, must soar infinitely above the situation that existed before the war.

The tendencies of capitalism to immiserate the proletariat which in the last few decades seemed to have been temporarily overcome will then assert themselves with the same terrible vehemence which they attained a century ago after the close of the world war in England.

But how completely different the proletariat stands today as compared to back then! From irregular outbreaks of despair against individual objects, which constituted the property of capitalists, from wild machine destruction and arsons, there has emerged a powerful, firmly ordered movement, on whose agreement to war policy governments everywhere place the highest value. One can think as one wants about co-operation between the government and the workers movement, but it is an extraordinary display of the latter’s power.

Such co-operation will nowhere be able to outlast the war but nevertheless the consciousness of their power will stay with the masses, even the most intimidated sections amongst them. And, at the same time, the ruin of the middle class must bring a massive influx into the masses, which will not lessen their bitterness. The layers which were until now the most firm dam of the establishment will most decisively long for its overthrow, which has become unbearable to them.

As Eckstein has already pointed out in his article on war and socialism, the subjective conditions, i.e. the minds of the people in given situation, are no less important that the objective conditions, and they are now growing closer to socialism, which in turn makes the realization of socialism possible.

The large business in industry will predominate more than ever while at the same time the control of banks over industry will become absolute. The disarray of the production process, however, will at the same time be so high that its regulation by governments, banks and communities will be indispensable.

That cannot happen without the application of large means, which the public has to bring, which however will be used to save capitalist profit.

At that point powerful struggles will light up over whether these policies are a means to secure capitalism and to transform it into an industrial-feudalism or whether state regulation of production will serve the proletariat rather than capital, and thus will be a socialist one.

These struggles will culminate in the struggle for political power. If the proletariat wins then socialism is moved within tangible reach.

Such are the perspectives which we today have to reveal to the proletariat. As bold as they are, they are far less illusionary than the bourgeois state of a future Mitteleuropean barracks state for which an array of socialists are now trying to win the working class. The idea of a Mitteleuropa is carried by a conviction that the coming peace can only be a truce which provides space to arm oneself for the next war.

We counter that idea with one of peace, which allows friendship and free intercourse with all peoples. We counter it with the struggle for socialism, which warrants us eternal peace.

Translated by Noa Rodman