Between January and October 1850, Karl Marx wrote a series of four articles on the revolutionary situation in France for the Neue Rheinische Zeitung, which were collected and published with the dreadfully uninspiring title Class Struggles in France: 1848-1850. Decades later, in 1895, the book was re-issued and Engels, months before his own death, wrote a new introduction for the book. The introduction is now perhaps more famous than the book itself, and probably for good reason. The Class Struggles in France, being written at the same time the events they described were occurring, was a piece of truly contemporaneous materialist history; Engels, in his introduction, noted this and said the following about the difficulty of writing such pieces:

If events and series of events are judged by current history, it will never be possible to go back to the ultimate economic causes. Even today, when the specialised press provides such rich material, it still remains impossible even in England to follow day by day the movement of industry and trade on the world market and the changes which take place in the methods of production in such a way as to be able to draw a general conclusion for any point in time from these manifold, complicated and ever-changing, factors, the most important of which, into the bargain, generally operate a long time in realms unknown before they suddenly make themselves forcefully felt on the surface. A clear overall view of the economic history of a given period can never be obtained contemporaneously, but only subsequently, after the material has been collected and sifted. Statistics are a necessary auxiliary aid here, and they always lag behind. For this reason, it is only too often necessary in current history to treat this, the most decisive, factor as constant, and the economic situation existing at the beginning of the period concerned as given and unalterable for the whole period, or else to take notice of only such changes in this situation as arise out of the patently manifest events themselves, and are, therefore, likewise patently manifest. So here the materialist method has quite often to limit itself to tracing political conflicts back to the struggles between the interests of the existing social classes and fractions of classes caused by economic development, and to demonstrate that the particular political parties are the more or less adequate political expression of these same classes and fractions of classes.

Today these words still very accurately describe the limitations that writers of current materialist analyses must face, even in spite of the major advances in communication that the Internet, television, and cell phones have both blessed and plagued the modern journalist with. We are still not able to perfectly access information about current situations immediately, despite the promises of avid technophiles; we must still write current history based on assumptions and information of dubious quality. Nevertheless, in order to orient ourselves for political action, it is still necessary to swallow one’s pride and write analyses that one knows are probably wrong.

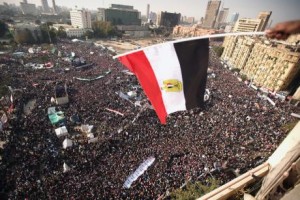

In the case of revolutions, both of these things — difficulty and necessity — are exacerbated. Information is harder to come by and what information you get is guaranteed to be biased (since everyone, including the people who spread such information, have a stake in the issue). However, it is still not possible to ignore such events, even less because as socialists we are revolutionaries first and foremost. So it must be with what is probably the most written-about political process going on today: no, not the royal birth (we know too much, not too little, about that!), but the situation in Egypt.

As per the title, the following is purely provisional. What I’m writing will probably be disproved rather quickly given my own lack of knowledge of the ground situation, being an American living thousands of miles away from Egypt. I make no attempt to know what is really going on in Egypt better than Egyptian comrades, and the people who must ultimately decide the course of action to be taken are them, not people such as myself living in the West (while writing this, however, I was lucky enough to get to speak with an Egyptian comrade on our IRC channel who went by the handle of jackparow, and I consulted with him about some points before I put them in here). This piece will almost certainly not be as long-sighted and timeless as The Class Struggles in France (nor do I hope it will be, because that would frankly just lead to a lot of embarrassment). Nevertheless, I think it is important that there is debate about Egypt within the Western left so that we can get a better understanding of the situation in Egypt and so we can engage in more heartfelt and effective solidarity — that is what this article is intended to contribute towards.

The Coup d’État

On the third of July, 2013, following days of protests on the streets, Abdul Fatah al-Sisi, the commander-in-chief of the Egyptian Armed Forces and the Minister of Defense under president Morsi, announced the deposition of the Morsi government and the switch to army rule under the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces1. For the past 21 days, all political events in Egypt have been related to the coup, and its fallout is likely to dominate Egyptian politics for the foreseeable future. Therefore, it is necessary to answer the question, what caused the coup? To answer this question, we need to go back and look at the larger social forces which aligned together to produce this event.

What is arguably the main reason is the rejection of political “bridge-building” by members of the Brotherhood elite. As Esam al-Amin notes2,

[the Muslim Brotherhood] reneged on several promises to its secular and liberal coalition partners, including to not contest the majority of parliamentary seats, field a presidential candidate or exclude others in the composition of the Constitution Constituent Assembly.

Furthermore,

Morsi and the MB did not adhere to their promise of full partnership in governance. Many of the youth and opposition groups felt that the president and MB leadership were not genuine in their outreach and only sought their participation for cosmetic reasons. Even their Islamic partners such as the Salafist Al-Noor Party complained that the MB wanted to monopolise the major power centers in the state.

The Egyptian Revolution of 2011 was a popular, democratic revolution: its aim to was overthrow the restrictive military regime, and to this extent it was supported by the liberal bourgeoisie, urban intelligenstia, and elite members of the Muslim Brotherhood (which had been an illegal organization since the 1950s with the attempted assassination of general Nasser), all of whom wanted a larger role in governing the country.

So when, in the ensuing elections, the Muslim Brotherhood not only won but excluded the other sections of the victorious bourgeoisie from the new government, the opposition parties were naturally very upset. The opposition was primarily concerned for a piece of the political pie; hence the ultimatum given by the SCAF after the June 30th protests, and not merely a coup to begin with3.

When the coup finally did happen, the opposition parties worked in accordance with the bourgeois-democratic principle which they thought was so egregiously violated, i.e. the right for all sections of the bourgeoisie to lord over the state and exploit the political process. Two key questions in the new “political roadmap” also stem from this: “reconciliation” and “technocrats.” With regard to “reconciliation,” the leader of the Egyptian Social-Democratic party said in an interview with Al-Ahram, the state news agency, that

We tried to reach [the Brotherhood], we said they are included. We don’t want revenge, we want to have reconciliation, which we said on TV and radio repeatedly. Most of the secular forces, said this. The Brotherhood doesn’t reach out to us: they don’t answer anything. We would love to have reconciliation with them, we would like them to join the political arena, as a normal regular party, like the others.

Many other parties in the National Salvation front, and of course al-Nour, the Salafist party, expressed similar sentiments. These opposition parties are fine with the Brotherhood repressing through the state — as long as they are given the opportunity as well. This sentiment echoes with the demand for “technocratic” interim leaders, who do not belong to any party in particular; many of the new appointments are indeed technocrats4.

The actions of the Muslim Brotherhood were key in alienating the other sections of the Egyptian elite, which led to their incessant attempts to agitate against the government and, in the end, their support for the coup.

There is also the question of the extent of the Brotherhood’s control of the state apparatus through its political wing, the Freedom and Justice Party. Opposition parties may be aligned against the government, but they cannot actually succeed in overturning it unless there is something they can exploit to do so. In the case of Egypt, it was the Brotherhood’s own weakness within the state. In the above interview with Al–Ahram, the former Egyptian Minister of Planning and leading member of the Muslim Brotherhood, Amr Darrag, revealed how aligned the state was against the ruling party5:

The president had maybe 25 percent control, but not more than that, and the control he had related to his power of legitimacy rather than physical power. The security forces, the police force was totally against him, not protecting, not doing that it should be doing, the military was concentrating on building the military establishment itself, they were not interfering on the surface, the judiciary was totally against us, and that was repeatedly proven, of course the media all the time, and the deep state.

The Muslim Brotherhood had taken power in a state that was deeply hostile to it. The military had a long tradition of repressing the Brotherhood, and the judiciary was packed with former Mubarak officials. Both institutions worked against the government, and when the president attempted to struggle against the judiciary, the opposition took the chance to denounce it as attempting to undermine the state and achieve its total domination; in reality the Brotherhood was very far from dominating the state. To quote al-Amin again, “the MB did not control the military, the intelligence, the security apparatus, the police, the diplomatic corps, the banking system, or even the bureaucracy.” Al Jazeera reports6:

Egypt’s transition has been likened to shaking the foundations of the old regime without dismantling it. That would require structural change that some argue has been prevented by what has been called “the deep state”.

The police are said to be one part of the deep state. Their leadership has not changed since the revolution and some have accused them of working against Morsi by not fully deploying during his presidency. The judiciary is another, as many of Egypt’s senior judges were appointed during the Mubarak era.

The military apparatus is of special concern here. The military is not only an active player in Egyptian politics, but is an economic power in its own right as well; many Egyptian generals are not merely generals, but also quite wealthy individuals. Additionally, the Egyptian military controls significant parts of the economy through patronage and outright ownership; the military is estimated to account for 40% of the total economy7. Furthermore, and most importantly, it is de facto absent of civilian control: hence it was able to move so freely against the government. Most importantly, however, the military has traditionally been at odds with the Brotherhood. The military, in this situation, seeks to control the political situation as much as possible for its own benefit. It is in this self-interested capacity that it turned against Mubarak to save itself, and it is in this capacity that it got rid of the Brotherhood, which proved to be too independent.

In short, the Brotherhood had not only the opposition aligned against it, but also the state apparatus itself, including both the fuloul (supporters and remnants of the former Mubarak regime) in the bureaucracy and the judiciary, but also the self-interested military forces.

However, as Darrag also notes, “The army would never have done this without the endorsement of the US, so we didn’t even meet [Deputy Secretary of State] Bill Burns when he came because we know quite well that he is part of the scheme.” The United States government provides $1.3 billion out of the Egyptian military’s $5.85 billion budget, or roughly 22% of their its entire budget. Moreover, the United States has been implicated in an Al Jazeera exclusive in the funding of anti-Morsi groups the senior opposition figures, including some of the leaders of the Tamarod group which organized the June 30 protests8. In the aftermath of the coup, the United States has refused to label whether or not the military overthrow of an elected government in Egypt constitutes a coup d’état9, and the furthest it has gone in opposition to the coup is delaying the delivery of four F-16 jets to the Egyptian military10.

The objective of the United States in Egypt is to have a government which is stable and compliant — in other words, it wants a client state. Prior to the coup, the United States was widely seen among Egyptian socialists as attempting to do this with the Muslim Brotherhood. However, basing ourselves on what we know about the situation, it seems likely that the United States found that the opposition — and the military — are more reliable allies than political Islam, and hence has thrown its lot in with them when they decided to make a move.

So, then, the coup d’état appears to be the convergence of the following factors:

- The systematic exclusion of certain elements of the bourgeoisie and the urban intelligentsia, and their subsequent alienation and alliance with the military and fuloul

- The opposition of the state apparatus and especially of the military to the Brotherhood, and the consequent lack of control the Brotherhood had over their actions.

- The United States’ interest in an Egyptian client state and clout within the Egyptian military and opposition groups

However, there is a fourth, unexamined element to all these political processes, any analysis of which needs to take into consideration: the Egyptian working-class, which has played a heroic role in the struggle.

The Proletariat

The Egyptian proletariat has so far played in enormous role in the major political events of the Egyptian revolution. In 2011, it was working-class action which provided the “muscle” for the revolution. The liberal bourgeoisie and the Muslim Brotherhood elite were able to overthrow the Mubarak government by riding on the working-class discontent stemming from its own exclusion from politics under the dictatorship and its increasing economic destitution under the government, which had been expressed prior to 25 January in a number of strikes, most notably the 2008 general strike. What erupted in 2011 was waves of strikes and labor action intended to bolster the political movement and to gain better conditions of life11 12.

However, after the overthrow of Mubarak, the workers did not simply stop striking; they took the demands raised by the revolution — of political democracy, of social justice, of better living conditions — seriously. The bourgeoisie was eager to put an end to the upheaval unleashed on the 25th of January as soon as possible, and the military (which had assumed control after the overthrow of Mubarak in order to save its own reputation) demanded an end to the strikes13. It even passed a decree criminalizing protests and strikes14. The bourgeoisie, which had previously relied on the proletariat to make its revolution, fell into an inevitable conflict with it, and both under the military government and the following government of the Freedom and Justice Party/Muslim Brotherhood workers engaged in numerous strikes for the realization of their demands for higher wages and better living conditions; the textile workers in El-Mahalla in particular acquired a militant reputation for their numerous actions. The working-class everywhere was in an uproar, and the bourgeoisie attempted to put them down; the deputy president of the Independent Union of Workers in the Cairo Water Company, Muhammad Hardan, wrote of some of the retaliation under the Morsi government15:

I witnessed some of this repression first hand, such as the smashing of the sit-in at Alexandria Cement using police dogs. I met workers from Beheira Joint Stock Company who hadn’t been paid their wages for 8 months. The petroleum companies sacked large numbers of workers: my colleague in the union didn’t get the money he was owed for 6 months. I was myself referred for investigation because I spoke to the national press about the demands of the Water Company workers. Others of my trade unionist colleagues have been transferred to different workplaces or denied work appropriate to their level of qualifications. A colleague of mine from the Alexandria Water Company was kidnapped and tortured because he took part in a protest. Another colleague from the Water Company was injured after being attacked and beaten up.

So, then, it is clear that the bourgeoisie attempted to contain the vast wave of working-class anger — and failed. Despite numerous crackdowns, the bourgeoisie was unable to curb working-class action. Nevertheless, the proletariat in Egypt still did (and does) not have a clear independent leadership or a clear sense of class consciousness. Hannah Elsisi, an Egyptian political activist, stated in an interview with the International Socialist Network16

Notions of class have nowhere in Egypt’s history (save for short spells in the 1890s and 1920s-30s) asserted themselves over political, cultural or socio-religious considerations. It is difficult to speak of a workers’ party when we cannot speak of any more than 700,000 to a million Egyptians who identify with this notion at the most basic level.

It is this lack of clear direction that allowed the 2013 coup to be carried out.

As the political opponents of the Morsi government — the liberals, the military, and the United States — began to align, they were able to once again direct working-class anger into a venue useful to them. The Egyptian working-class had good reason to be opposed to the Morsi regime. In an interview with the general secretary of the Communist Party of Egypt by the central organ of the Tudeh Party of Iran, the general secretary stated the following about the Brotherhood’s economic policies17:

The Muslim Brotherhood implemented the same policies on the continuation of the privatization program and the liberalization of prices, and did not raise the minimum wage even though it was one of the first demands of the revolution. They even reduced the taxes on businessmen, continued the privatization of services and refused to implement the health insurance program. They insisted on selling and mortgaging the assets of Egypt and its institutions through the project of “Islamic bonds” which they rushed to pass in the Shura Council [the upper house of parliament] controlled by Muslim Brotherhood. The most dangerous position was their refusal to pass the law to ensure freedom to form unions, which they had agreed upon with all political forces and trade union currents before the revolution, and replaced Mubarak’s men in the government-controlled General Union of Egyptian Workers with their own men.

The result was that “the number of social protests (strikes, sit-ins, demonstrations and protest pickets) reached 7400 – by Mohamed Morsi’s own admission – during last year.” Even the textile workers in El-Mahalla even went on strike to protest the Muslim Brotherhood18. It was this legitimate proletarian opposition to the Brotherhood government that the bourgeois opponents of Morsi oriented against him in the June 30-July 3 protests.

It must, however, be emphasized that the problems facing the Egyptian proletariat do not stem from the special and particular evilness of the Muslim Brotherhood elite. On the contrary, the conditions of the Egyptian working-class stems directly from the antagonism between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, the latter of which the liberal opposition and the military leadership both belong to. Therefore, the coup is merely a switching out of leaders, and the fundamental task of the working-class in Egypt for its own betterment is to break from such bourgeois leadership.

However, the popular nature of the June 30 events, while of course still existing and very important in analyzing them, should not be exaggerated. Going back to Asam al-Amin’s account of the make-up of the protests, we see they did have a popular character:

Although the protesters did not include Islamist groups, they were diverse. Many youth groups were represented, voicing their frustration of being marginalized and their demands neglected. Many were ordinary citizens alienated because of economic hardship and the lack of basic services.

… However, there were also less valorous elements present at the events, as al-Amin notes that

[…] it was also clear that many were fulool and Mubarak regime loyalists as the picture of the former dictator was prominently raised and hailed in Tahrir Square amid chants in his support. Many were also former and current security officials who showed up in their uniforms. Even two former Interior Ministers who served during the military transitional rule and former regime were leading the protests as revolutionaries, even though they were charged by the youth groups at the time with murdering their revolutionary friends and comrades. Many protesters were also thugs hired by NDP politicians and corrupt business people.

Additionally, some of the claims of the size of the June 30 are becoming increasingly untenable. Al Jazeera points out that the only three widely accepted figures for the size of the protests — 14 million, 17 million, and 33 million (the last of which is 39% of Egypt’s estimated population!19 — all originate from military officials, two of whom are completely anonymous20. There have also been suspicions that the military has been intentionally sabotaging the economic situation in Egypt to stir popular discontent against the Brotherhood, especially with regard to the endemic fuel shortages21.

In a repeat of the history of the 2011 revolution, the bourgeoisie has once again moved against the proletariat. The new minister of manpower and the former head of the independent trade union federation has called for an end to the waves of strikes that started with the June 30 events22. If the past is any indication, the strikes won’t stop as the working-class of Egypt seeks a true realization of the social justice promised in the slogans of the revolution.

The Future

To borrow a Lenin quote that has been chronically overused in relation to the Egyptian revolution (but is nevertheless quite fitting!),

There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.

In Egypt, decades are now happening in weeks. The future movements of the various social elements in the revolution are unfolding before our eyes at an incredible rate. How the revolution will ultimately end is indeterminable at this point. However, it is possible to make some estimated guesses (although they remain only this) about the political situation in the near-term.

The political fortunes of the Muslim Brotherhood in the near future, for example, look bleak. In an attempt to force the Muslim Brotherhood into a confrontation, Al-Sisi called for mass rallies to give him a “mandate” to confront “violence and terrorism.”23 At the same time, the army issued an ultimatum to the Brotherhood to participate in the “political roadmap” in the next 48 hours after the rallies, with the catch being that if they refused the army would be much tougher on their protests. Simultaneously with the rallies, the military announced charges against the deposed president Morsi; he was accused of having links to Hamas24. After the rallies, there were allegedly over 120 people dead and 4,500 injured, most of them MB supporters25.

The Muslim Brotherhood, of course, has survived tough periods before, and it is not inconceivable that they will once again become a force in Egyptian politics. However, the recent crackdowns against the Brotherhood — from the murders by the army, to the imprisonment of Morsi, and now, even as I type, the government is making further plans to disperse Morsi protesters26 — suggest that the army is making moves to eliminate its influence. Perhaps more damaging to the Brotherhood is a loss of public appeal; in April 2013, before the coup, Morsi’s approval rating fell to 47%27, and in July 2013, and after the coup, an overwhelming 71% of Egyptians did not sympathize with the pro-Morsi protests (61% were “very unsympathetic”)28. It is safe to say, therefore, that for the foreseeable future the Brotherhood is politically dead.

The army, on the other hand, appears to be making moves towards towards restoring army rule. In a statement by the Revolutionary Socialists group outlining their reasons for not attending the rallies on the 26th of July, they made the following observation29:

If Al-Sisi has the legal means to do what he wants, why is he calling people into the streets? What he wants is a popular referendum on assuming the role of Caesar and the law will not deter him.

The military’s increasingly active role in politics and Al-Sisi’s direct appeal to the masses indicates they are attempting to increase their own control over the situation. In an alarming move, they are beginning to censor media which is too “anti-army.”30 The military will likely attempt to use clashes with the Brotherhood — “terrorists,” in Al-Sisi’s words — to gain more and more power, all in the name of protecting the revolution. This, however, will bring it into contradiction with its current liberal allies, who wish for a parliamentary republic; unless the army has enough popular support, it will probably opt for a parliamentary republic where it can control the process from behind the scenes with its liberal allies.

At the same time, it is indubitable that the working-class will continue its own struggle for the implementation of true social justice — a struggle that will bring it into conflict, once again, with the bourgeoisie which thought it could control it. Already there are voices among the working-class which are skeptical of the army. Fatma Ramadan, a member of the executive committee of the Egyptian Federation of Independent Trade Unions (whose majority — of which she was not a part of — voted to support the army rallies), wrote31:

The leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood are planning crimes against Egyptian people on a daily basis, which have caused the killing of innocent people, while the army and the police are facing these with brutal violence and murder. But let each of us remember, when do the army and police intervene? They intervene long after clashes have begun and are almost coming to an end, after blood has been spilled. Ask yourselves, why don’t they prevent these crimes committed by the Muslim Brotherhood against the Egyptian people before they start? Ask yourselves, in whose interest is this continuation of fighting and blood-letting? It is in the interest of both the leadership of the Muslim Brotherhood and the military together. Just as the poor are cannon-fodder for wars between states, Egypt’s poor, workers and peasants, are fuel for internal war and conflict. Has not the doorman’s innocent son been killed in Mokattam, and in Giza as well?

In the upcoming period, the Egyptian working-class will undoubtedly face enormous challenges. One of these is breaking free of the dominance of the military and the liberals on one side and the Islamists on the other. Nevertheless, it is a task which must be accomplished, and one which in the coming days, weeks, months, and perhaps years, the Egyptian workers will accomplish as the victorious sections of the bourgeoisie prove not only in words but in deeds the irreconcilable antagonism between classes. The struggle against the Brotherhood has been more or less ended for now, as their anti-working-class orientation was shown and their reign forcibly ended by an alliance between the opposition and the military; the struggle against these same victorious forces has now begun. In this struggle, it is the duty of all socialists to support the Egyptian working-class.

Addendum

(There is, of course, another path for Egypt to take, which is civil war. However, it’s too difficult to say at this point whether this is a likely road to the situation to unfold into; however, if Al-Nour aligns with the Brotherhood against the military, it’s possible).

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-23173794 ▲

- http://www.counterpunch.org/2013/07/05/in-egypt-the-military-is-supreme ▲

- http://edition.cnn.com/2013/07/01/world/meast/egypt-protests/index.html?hpt=hp_t1 ▲

- http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/1/64/76609/Egypt/Politics-/Whos-who-Egypts-full-interim-Cabinet.aspx ▲

- http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/1/151/77038/Egypt/Features/QA-Egypts-titans-defend-their-party-positions-.aspx ▲

- http://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/insidestory/2013/07/201372675154613788.html ▲

- http://www.counterpunch.org/2013/07/04/egyptian-military-a-state-within-a-state ▲

- http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2013/07/2013710113522489801.html ▲

- http://www.cnn.com/2013/07/25/politics/obama-egypt ▲

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-23442947 ▲

- http://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2011/02/20112913546831171.html ▲

- http://www.democracynow.org/2011/2/10/egyptian_uprising_surges_as_workers_join ▲

- http://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2011/02/egpt-f16.html ▲

- http://www.egyptindependent.com/news/new-egyptian-law-criminalizes-protests ▲

- http://menasolidaritynetwork.com/2013/07/05/egypt-after-tasting-freedom-we-will-not-be-slaves-again-a-trade-unionists-view-on-morsis-fall ▲

- http://internationalsocialistnetwork.org/index.php/ideas-and-arguments/organisation/swp-crisis/international/166-hannah-elsisi-interview-on-the-fall-of-morsi-live-from-cairo ▲

- http://www.solidnet.org/egypt-communist-party-of-egypt/cp-of-egypt-interview-with-comrade-salah-adli-general-secretary-of-the-egyptian-communist-party-by-nameh-mardom-the-central-organ-of-the-central-committee-of-the-tudeh-communist-party-of-iran-en ▲

- http://www.albawaba.com/news/egypt-labor-469674 ▲

- http://www.capmas.gov.eg/?lang=2 ▲

- http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2013/07/2013717115756410917.html ▲

- http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/11/world/middleeast/improvements-in-egypt-suggest-a-campaign-that-undermined-morsi.html?pagewanted=all&_r=1& ▲

- http://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2013/07/22/egyp-j22.html ▲

- http://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2013/07/201372517948899595.html ▲

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-23464036 ▲

- http://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2013/07/27/egyp-j27.html ▲

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-23478947 ▲

- http://www.dailynewsegypt.com/2013/04/07/baseera-poll-percentage-of-egyptians-who-disapprove-morsys-performance-reaches-record-high ▲

- http://www.baseera.com.eg/pdf_poll_file_en/Sympathy%20Towards%20Demonstrations%20in%20Support%20of%20Former%20President_en.pdf ▲

- http://socialistworker.co.uk/art/33983/Statement+from+Egypt’s+Revolutionary+Socialists%3A+Not+in+our+name! ▲

- http://www.egyptindependent.com/news/anhri-condemns-al-shorouk-censoring-anti-army-article ▲

- http://menasolidaritynetwork.com/2013/07/26/egypt-do-not-let-the-army-fool-you-independent-union-leader-speaks-out ▲