Why, in a social relation involving the domination of a non-elite by an elite, does challenge to that domination not occur? What is there in certain situations of social deprivation that prevents issues from arising, grievances from being voiced, or interests from being recognised? Why in an oppressed community where one might intuitively expect upheaval, does one instead find, or appear to find, quiescence? [pp3]

The questions that open Power and Powerlessness, John Gaventa’s investigation of social peace and rebellion in a desperately poor Appalachian valley, remain on the lips of radicals everywhere, some 30 years from publication. The crisis has been a stark demonstration that economic deprivation does not necessarily impel the deprived into conflict with elites. The questions that surround the fraught transition from ‘class in itself’ and ‘class for itself’ deserve to be dominant strands in progressive strategy but are rarely answered coherently. While revolutionists lurch from outlandish overoptimism to dark mutterings of betrayal, the once centre-left has dropped all interest in the issue, preferring positioning to power-building.

And so, to better understand the actual mechanisms behind protest and acceptance, we should turn to work such as this. Power and Powerlessness offers a detailed and thorough assessment of power dynamics in an Appalachian valley, where manmade poverty sits alongside immense natural wealth. Gaventa discards moralistic and culture-based explanations for persistent social peace, arguing instead that quiescence is produced and maintained by power relations. He adopts a ‘three-dimensional’ view of power, which sees power as residing not only in the capacity to prevail in political contests but also to determine what issues become subject to politics and, indeed, whether or not issues and problems can be identified as such by those they affect.

If the victories of A over B in the first dimension of power lead to non-challenge of B due to the anticipation of the reactions of A, as in the second-dimensional case, then, over time, the calculated withdrawal by B may lead to an unconscious pattern of withdrawal, maintained not by fear of power of A but by a sense of powerlessness within B, regardless of A’s condition. A sense of powerless may manifest itself as extensive fatalism, self-deprecation, or undue apathy about one’s situation… The sense of powerlessness may also lead to a greater susceptibility to the internalisation of the values, beliefs, or rules of the game of the powerful as a further adaptive response – i.e. as a means of escaping the subjective sense of powerlessness, if not its objective condition. [pp16-17]

Also crucial is the reflexive result of action upon understanding. Citing Pizzorno “class consciousness promotes political participation, and in its turn, political participation increases class consciousness”, Gaventa infers that “those denied participation… also might not develop political consciousness of their own situation or of broader political inequalities.” [pp17-18]

His case study offers ample support for these hypotheses. The characteristics of the area, with an absentee capitalist class, a local elite made up of intermediaries with external capital, and a narrow range of work opportunities produce strong dependence among the impoverished. The political process remained stagnant, with three elite political dynasties dominating local politics.

Fatalism pervades popular perceptions, with people tending to avoid conflict from fear of reprisal or a sense that nothing can be achieved. ‘You can’t do anything about it and the end is near at hand anyway”, says one woman of the destructive effects of strip mining. [pp206]

At its most effective, power makes adherents of the oppressed. The coal owners, one miner remarked bitterly, “worked their men for a song – and the men sung it themselves” [pp93, empasis in original]. Quiescence is self-reinforcing; the less precedent for action, the less compelling its case, while each successive defeat lays upon the last, smothering the aspirations of the downtrodden. On the rare occasions that struggle does emerge, other mechanisms can come into play to keep the poor at bay.

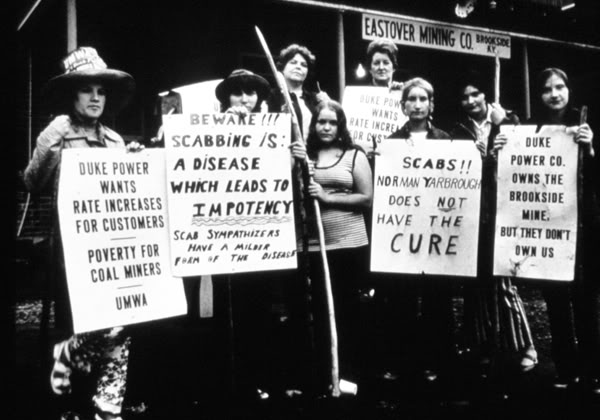

When popular challenges to the status quo did emerge, it was through the development of new forms of organisation and consciousness. The Communist Party-influenced National Mineworkers Union made broad inroads among the miners, growing with a speed and militancy that amazed the organisers. But the resultant strikes ended in defeat, with the elite combining violent repression, State and extra-judicial, with control over information and manipulation of the community’s religiosity and patriotism against their champions. From then on, words like ‘Communist’ and ‘Dual Unionist’ could be deployed as rhetorical weapons against new uprisings.

Some thirty years later, a community centre and Community Action Board, both developing from the Kennedy-era War on Poverty, were instrumental in bringing the population into greater recognition of the power dynamics that shaped their world and a greater eagerness to change them.

In the space of about five years, through a process of deciding upon and carrying out actions, definitions of interests shifted from those involving little conflict against the existing order (garbage collection) to the development of alternatives to that order (a factory, clinics) to the notion of challenging the order itself (land demands)… But as actions were taken by the community itself to solve its problems, it faced further obstacles from government and corporate interests. The notion of contradictory interests began to be emerge, and external forces were seen as being responsible for internal conditions.[pp211-212]

Gaventa explains this process with reference to Paolo Freire’s notion of ‘limit situations’, which set the boundaries for what people think is possible. “As reality is transformed and the limit acts are superseded, new ones will appear, which in turn will invoke new limit acts”. [pp209, citing Freire]

In the end, however, these and other struggles were effectively contained by the elite. Violence, whether real or imagined, economic vulnerability and social isolation were effective tools at keeping the rebels in their place. Control of local politics could be used to orchestrate State repression, ignore vigilantism, or enable simple out-manouevring, to disempower and contain the protests. The most ignominous chapter sees the miners of the area, among the poorest in the country, colluding in the corrupt rule of W.A. Boyle, president of the United Mine Workers and carrying out the murder of Jock Yablonski, a reform candidate who called for greater militancy and democracy.

However depressing, for radicals, defeat should be instructive, drawing us to a better analysis. Instead of asking peevishly, ‘why does rebellion not occur?’, we must instead pose the question, ‘how can rebellion occur?’. The question must interrogate the power relations that shape our world, seeing that the path to socialism is one of social empowerment, to be accomplished through the creation of lasting changes in popular organisation and consciousness. It is, in effect, the creation of a popular subject capable of wielding power in its own interest. In the author’s words, “Rebellion, to be successful, must both confront power and overcome the accumulated effects of powerlessness.” [pp258]