Decentralisation has become a fashionable notion in modern politics, finding common expression in both the libertarian left and the conservative right.

It seems that Greenpeace, local-food advocates 1, anarchists and even Tories 2 are united in the belief that decentralisation is almost always good. The days when Marxists felt confident in championing centralisation are long gone.

The question of centralisation has doubtless been made murky by the slow bureaucratic behemoths of both the state in the USSR, and large corporate entities elsewhere with centralisation becoming synonymous with a kind of arbitrary and purposeless power with little responsiveness to those unfortunate enough to have to interact with it.

Nevertheless, the impetus to centralise may be either progressive or regressive depending on the circumstances, while the notion that decentralisation is, on the whole, better does not stand up well under closer inspection.

The Localists

Amongst environmental advocates decentralisation is tantamount to a universal silver-bullet. The story goes that we will grow food locally, produce energy off-the-grid and be as self-reliant as possible. Sometimes the advocates will advance the use of local currencies, and in some circles further claims are made about the possibility of revolution if only we are no longer dependent on others in remote places and the products which they make.

This idea of localism in radical political currents is not at all new. Ideas of recapitulating imagined golden eras of hearty down-to-earth living and the moral advantages that both proper work and a life devoid of modern evils have been popular since at least the 19th century. This romantic tendency of a backwards looking rebirth is visible in everything from the hippies’ attempts to go back to the land, Kropotkin’s veneration of the Mir, the Kibbutzniks’ approach to reclaiming dignity in self-reliance and, more darkly, in the radical right wing such as the ecological wing of the Nazis and third positionist ideals of national separatism.

Food localism talks about the advantages of growing our food in a particular locality. The locality in which you grow a food is, however, contingent on the qualities of that locality. For instance, if we take a place in which rare earth metals are found, we’re unlikely to be very near to arable land. Are people there supposed to feel guilty for getting non-local food while supplying others with rare earth metals necessary for modern computers? Some local food advocates do in fact think that we should stop producing such modern conveniences, but then one must ask how far back to roll the clock?

There may be ways of growing food locally using hydroponics and some automation, coupled with long-range irrigation, but then the question of what local food is supposed to achieve must again be asked. It’s quite possible to have greenhouse farmed tomatoes in Alaska, but the cost in energy is quite likely to be higher than transporting them from Florida. If the question is about energy, maybe we should be talking about food energy. But then is all energy created equal? Clearly it’s more desirable to be using free solar energy to grow tomatoes than coal. The question can not be effectively collapsed into a simple equation of local being good 3.

The question of food security is also often raised by local food advocates. The NATO countries, however, have taken serious steps to ensure that they would be food-secure in the advent of major war. So then the question is what scale of food security are we looking at. Are we trying to make each major city food secure without access to its hinterland? With access to its hinterland? It is a rather collapse driven viewpoint if we’re trying to imagine how we can sustain ourselves in almost arbitrary food disaster scenarios.

Energy

Greenpeace has promoted the notion of radical decentralisation of electricity as a major way of cutting electricity usage and increasing efficiency 4. Unfortunately they appear not to have consulted any engineers. For thermodynamic reasons it’s much more efficient to have a large very hot source of power generation. There are huge economies of scale that can be achieved through centralisation. Further, they claim that by decentralising, grid miles can be reduced. However very high voltage DC current from a centralised plant can allow much greater transmission efficiencies than lots of small AC current transmission lines.

Technologies such as Combined Heat and Power (CHP) which can use waste-heat from massive generators (including nuclear power plants) to distribute heat to whole cities are excellent examples of both economy of scale and centralisation being superior. Capitalists who have looked into CHP have rejected it on the basis that it’s very difficult to meter transmitted heat usage, meaning that it’s difficult to exploit for profit, but for socialists, this sort of use-case is perfect, as waste heat can hardly be wasted! Here we have a good example where a coordinated cooperative and large scale centralised policy can make for radical gains in efficiency.

Wind and solar power are favourites among decentralisation friendly environmentalists and are presented as methods of allowing a radical decentralisation of our power needs. This, advocates say, would mean that we could be self-sufficient and it would be an attack on capital power. In point of fact, wind and solar energy require vastly more centralisation to be usable than almost any of the technologies localists appear to be against. Wind and solar are intermittent power sources which means they would require generation over vast geographical scales with sophisticated load balancing. Even then they would not be sufficiently stable unless we added some sort of power storage which is almost invariably going to be pumped water. Vast pumped water storage would require huge reservoirs with scales on the order of the size of the biggest hydro-power dams. This will require centralisation of infrastructural coordination on a scale that has never before been seen. A recent study at the University of Delaware which attempted a broad search of possible configurations using five years of solar and wind data came to the conclusion that there were feasible configurations but they required very large scale grid connectivity5. It may be that this is indeed what needs to be done to meet our energy needs in the safest manner, but it certainly will not be a point scored for decentralism.

By contrast, nuclear power is often said to be a centralising power, but nuclear can be decentralised practically far more than solar and wind. It’s simply that such a decentralisation would not be desirable for reasons of efficiency and safety. Instead it’s been kept centralised for the advantages of centralisation.

Decentralisation of living means increased transportation costs. The cost difference from fuel use for transportation for a city as dense as Moscow compared to a city as dense as Houston is around two orders of magnitude (or close to 100 times larger)6. This is waste compounded if we imagine many decentralised cities over a huge area.

Centralisation and Mathematics

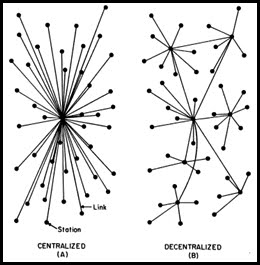

Some of the utility of centralisation and the disutility of decentralisation is caused by what are in fact immutable mathematical principles.

Europe used to have many different currencies and this provided a significant barrier to trade. The reason for this is that the use of n currencies in n countries requires the holding of n different reserves in n different countries leading to order n2 total reserve combinations. For 2 countries, this number is 2, for 10 it is 45. One can see that the scaling behaviour is costly as n becomes large. With many currencies there is a large overhead in management. Advocates of local currencies often do not realise the complications that would necessarily result from the adoption of a large number of local currencies.

Similarly, in the EU there are many languages and the EU body gives legal status of various types to many languages. For n languages in official use, we again require on the order of n2 translators. The overhead of this as opposed to one official language should be obvious.

In a confederal system where each entity must make agreements through treaty with its peers, there will be a similar difficulty of a vast number of overlapping and complicating treaties which require bureaucratic overhead and actually increase the standing and importance of the bureaucracy. This creates difficulties for those that would like a more transparent and democratic system. The EU manages to demonstrate many of these complexities.

Control theory is the interdisciplinary study of systems which have observables and controls. It is a very abstract mathematical way of viewing a large number of systems in which we want to understand how to control various outcomes given some number of control parameters. The controllability of the system relates to how well we can determine outputs with the control parameters at hand. In the general case, attempting to control an output parameter will require control parameters that are at the same scale as the output. This gives strong support to the notion that choosing global parameter outcomes will require global control and can not be done in a decentralised fashion. Intuitively, if we want to control global warming, we will require global methods of ensuring the amounts of CO2 produced – something which cannot be done in a decentralised way.

Centralisation and Polity

One of the primary complicating factors of the discussion of centralisation results from a lack of clarity regarding what is meant by centralisation. This problem goes back all the way to the discussions between Bakunin, Marx and others in the First International concerning the appropriate political formation.

The immediate knee-jerk rejection of centralism is often based on the completely sensible rejection of authoritarian rule. The term very often evokes the role of a dictatorship or monarchy embodied in a single person such as Stalin.

In order to clarify the meaning of centralisation it has been customary among the descendants of Leninism to use the term democratic centralism, a principle that was at least partly developed in the social democratic organisations in Europe and described explicitly by the Bolshevik party. This principle essentially calls for a unitary organisation with a democratic internal structure. Conflicts are resolved internally to the party and in this way paralysis is avoided, but with a coherent and unified direction.

The origin of the left support for centralisation in the Social Democratic Party of Germany was in the need to keep the rural areas from dominating the organisation. The SPD had unfortunately adopted a federalist basis giving geographic rather than purely proportionate representation 7. This lopsidedness strengthened the more conservative and reformist minded sections of the SPD and led to the call for centralisation by the urban radicals such as Luxemburg.

The fact that the Bolshevik organisation devolved so fantastically into authoritarianism (finally culminating with Stalin) has furthered confusion with regards to democratic centralism. In addition there have been numerous organisations which have taken the meaning of democratic centralism to characterise a later phase of the Bolshevik party organisation after it had become more rigid and less democratic through the process of the civil war. This later democratic centralism was really a pale shadow of what it had been before the brutality of conflict had moved it in a more authoritarian direction.

The principle of centralism when understood as a unitary organisation with democratic character is not less possible than having a democratic character for a federalist grouping. On the contrary, there are actually certain features of the former that make it more desirable. Firstly, the notion of the a geographic size and scope for a constituent of a federation presupposes a grouping which is, essentially, arbitrary. Why should the EU be a confederation of nations rather than a confederation of states. Why not break France up into districts, but leave Germany intact? The logic of a confederation can just as easily be seen as a gesture to the current dominance of nationalist and localist thought.

Since the groupings in which federations take place are essentially arbitrary, there is no more sense in a federation than the creation of a unitary organisation encompassing the entire region.

Now, some might complain that this ensures that the decisions that are made will be made in such a large grouping that the individual voice is drowned out. However, for decisions of great magnitude, e.g. how we might work out European rail transport, it only stands to reason that the voice of each person is only as great as the number of people in Europe. Attempting to solve this problem by regressing to individual local choices entails no advantage whatsoever. By decentralising we simply find ourselves with more control over decisions that don’t matter very much.

It makes sense that the entire polity does not micromanage affairs. A principle of subsidiarity, where decisions are made by the body of least size with competence over an area, ensures that local knowledge is taken into account and that the need for central bureaucracy is reduced.

There are many ways in which the central body can be obtained to ensure that it is as democratic as possible. One possibility is the selection of a large executive and legislative assembly by lot. This would ensure a representative selection of the population. It would guard against the production of both demagogues and monarchs and would have none of the current deficiencies which tend to favour representation of the more powerful section of the population.

Globalisation and the Global Spectre

Groups on the right see the true danger of globalisation as being represented in a global state – often with paranoid conspiratorial fears of the UN or some new world order.

The left has a more realistic view of where the real organs of power lie. In reality these fearful demons are largely embodied in trans-national corporations and global finance.

The similarity between the left and the right, however, is in the popular demands made to curb these threats. While there have been calls for alter-globalisation in some corners of the left, their practical organisational groupings have been very modest. During the anti-globalisation protests, the response was largely simply riots, with large numbers of Europeans from other countries coming to join in opposition to various meetings seen as representative of the political consensus of the global capitalist powers.

While these protests raised awareness and created difficulties for the ruling elite, they also were unable to present viable bases of power either to stop any particular policies, to force concessions, or even to retain some permanence or legitimacy.

From this period we have entered a global financial crisis and yet we seem to have descended further away from any global resistance. Instead the entire idea of a cooperative movement against the capitalist powers has been replaced with ideas of retreat.

The idea of even European parties or Unions of the left is considered far fetched or unworkable, or even, by many, undesirable. Instead we are left with slogans against the EU and for local autonomy.

This autonomy however can never be anything but illusory. Capital is still global capital no matter how devolved the political apparatus appears to be. As we have seen in Ireland, national sovereignty is no more than a joke when every decision in the Dáil must first be ratified by the bond holders or the entire country goes into default.

Similarly, any decision made regards the taxation rate of corporations or the rich is vetoed on the not entirely unreasonable basis that the corporations or rich will retreat to other locales. While it’s certainly true that only the extraordinarily wealthy would leave a country for tax purposes, it’s also true that because of the continually growing imbalances between the rich and poor this is a more significant threat than it otherwise would be.

What good then is a retreat to local sovereignty with the full right to control decisions of no consequence. The retreat itself has no meaning. In a situation such as that, it should be clear that the only direction is attack. We have to refocus on a centralisation of our movement to scales in which we can actually combat the problem.

Federation and Confederation

Federation is a confusing concept since it has been written about as meaning various things, from confederation (especially in the conceptions of anarchists) to centralism (as in the US federalists who were actually centralists).

Confederation is a term which denotes the looser affiliation of sovereign states that is present in bodies such as the EU or in several past attempts at anarchist political groupings as “federations”.

In practice, confederation is brittle. The EU is actually a large number of overlapping confederations formed by treaty. All of these have different functions which complicates each individual’s ability to reason about how things are suppose to happen and increases bureaucratic overhead for no reason whatsoever.

Economic Decentralisation

One of the more pernicious radical decentralist notions is the right to secession. This principle sees it as the right of some political unit to withdraw from the rest of society. It is hard to understand how this principle can be supported by socialists in light of the also ubiquitous slogans of “no borders” and the supposed lack of belief in national sovereignty.

The outcome of a political secession has historically often been incredibly destructive to the interests of the working class. However, it’s important to think about why such a secession might take place. The tendency towards support for economic localism is a tendency to support the continued divisions between groups. Since true autonomy is not realisable, it is merely an attempt to bring out illusory self-reliance. When self-reliance is no longer possible because of unforeseen crises the result will be catastrophe.

Let’s say a society did get all of its food from local production. In the event of a famine, the ability and infrastructure to effectively distribute food to the locality of the famine would not exist. Neither would people be producing surplus in the areas with large capacity for distribution elsewhere. Regions which might be extremely rich in resources like Lithium are an absolute necessity for the production of modern computer components. Yet these same places tend to be deserts and not useful for the production of food. How then should these places produce food effectively? Should Ireland be without computers such that we can ensure self-reliance? Should no-one be mining Lithium?

If we really take this notion to heart, we’re making a plan to recede technologically to agrarian times. A return to medieval technology would additionally be a return to a much lower population carrying capacity. The consequences of this decision would in fact be truly dire: millions upon millions of deaths. The more we centralise production, the more we can specialise and improve the capacity of production deriving from benefits of scale. This centralisation should of course be under the direction of the population through democratic structures.

The current situation of the economy is in many respects highly decentralised. The economic market is a vastly complex network of often small subsidiaries and groups which produce or coordinate production. It can’t really be that we mean to dissolve the economy into self-reliant micro-sections in any real sense. Sensible localists must mean to stop short of something so extreme. Nonetheless, these localising tendencies deepen views of sectional self-interests where progressives should instead be pushing for larger scales, greater unity and more cooperation across wider areas.

During periods of disruption these decentralising divisions can erupt dangerously. The Yugoslav republics came apart because of conflictual economic relations during a period of punctuated economic decline. It’s often been said that Tito held the Yugoslavian republic together; however, there are good reasons to reject this theory. Instead he helped to ensure his own power by setting up different groups in opposition much in the same way that Gadaffi encouraged tribal divisions. When economic stagnation and finally collapse set in, various organisations and bodies which had control over important resources stepped up to claim their sectional advantage while the entire system sank. Eventually Yugoslavia descended into a civil war in what had previously been a prosperous and peaceful region.

China should provide a powerful antidote to the idea that political decentralisation is in itself advantageous. Here, the move from the local decentralised authoritarianism of the Warlords towards a unitary state in 1949 was a progressive move. The finally constructed state was authoritarian in many respects and should not be viewed uncritically. However, for the working class and peasantry it was quite an improvement from the constantly warring authoritarian micro-states. The economic situation much improved under the centralisation of the Chinese state, with famine moving from a literally annual occurrence impacting huge sections of the population to something which only occurred for three years in total after 1949. This is not an aberration either; we can see many of these same dynamics taking place in many places in Africa.

Centralisation and Class power

It has become common to assume that capitalism prefers centralisation. This is true in some cases, yet capitalism has also proved flexible enough to use decentralisation to its advantage.

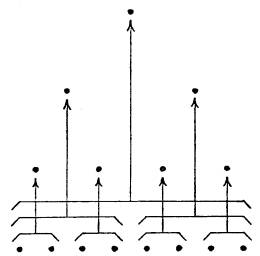

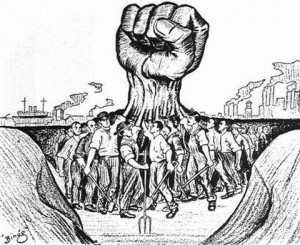

As Marx noted repeatedly, and as was echoed by Kautsky and many others, the process of capital accumulation, and the focusing of efficiencies by the creation of large efficient industries, leads to a natural centralising tendency. This centralising tendency was theorised to lead to class conflicts by an increasingly homogeneous proletarian class which had very little save their labour power, but which could grind capitalism to a halt with if that labour was withdrawn.

While this in fact did occur, especially in the early 20th century, capitalism was not destroyed by this conflict. Instead it modified its behaviour to decentralise when centralisation was to the advantage of the working class.

Over and over we see in history that resistance was present in the coal-miners, train drivers, tram drivers, factory workers and port workers. This is not a coincidence. The bottle-necks created by these organisations increased the power of the working class and decreased capital’s options in dealing with it.

Capital responded by increasing the relative quantity of constant capital (changed the organic composition of capital) in all of these sectors in order to disempower labour.

While the change in organic composition impacted all sectors and notably continues to deepen in factory labour, it is perhaps the most extreme in the case of the port workers. The amount of automation of ports through the use of containers and automatic cranes has left port workers a shadow of the previous labour juggernaut that it had been before.

In the case of train workers, roads were promoted, as roads involved independently contractible drivers, provided potentially many routes to the same place and could not as easily be blocked. They were essentially far more decentralised.

In manufacturing, capital moved into a post-Fordist phase, where it disaggregated large factories and created subsidiaries which would specialise in sections of the production. This decentralised the workers, keeping them in more manageable units and thereby giving capital more options: if one group attempted a strike, it would simply source parts differently. It also reduced the spread of unions by essentially creating fire-walls for protection between various sections of the production chain.

Conclusion

It is often noted that there are no panaceas. Centralisation is not always the appropriate principle and neither should decentralisation always be rejected. As a political principle neither is universally appropriate. It is politically very dangerous to raise such important concepts to the level of a principle, and we would do well to be more guarded in accepting decentralisation as advantageous in itself.

NOTES

“The absence of a centralized consultative assembly from which the government could receive grants of taxation made it necessary for the French Crown to bargain separately with each constituency. As a result the form and level of taxes varied from region to region. For example, sales taxes were levied on regions with commercialized areas, while communities living near war zones had to pay taxes specifically designated for defense. Had a central parliament existed, similar negotiations between central authority and the localities in which one locality received rights denied another would probably not have been approved. Thus, differences between the rights of various regions tended to be effaced through the English Parliament, whereas in France variations were often intensified, as each province negotiated with the Crown to protect its particular exemptions without regard for the costs consequently imposed on neighboring regions.” – The Fountain of Privilege

- href=”http://www.localfutures.org/publications/online-articles/bringing-the-food-economy-home”>Bringing the Food Economy Home ▲

- href=”http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2009/feb/17/david-cameron-decentralisation-tony-benn”>David Cameron hails Tony Benn in decentralisation plan ▲

- href=”http://works.bepress.com/lauren_kaplin/2″>Lauren B. Kaplin, Energy (In)Efficiency in the Local Food Movement: Food for Thought, Fordham Environmental Law Review (2012) ▲

- href=”http://www.greenpeace.org.uk/media/reports/decentralising-power-an-energy-revolution-for-the-21st-century”>Decentralising Power ▲

- href=”http://www.udel.edu/udaily/2013/dec/renewable-energy-121012.html”>Wind, solar power paired with storage could be cost-effective way to power grid ▲

- Newman & Kenworthy, 1989 ▲

- Karl Schorske, German Social Democracy, 1905-1917: The Development of the Great Schism ▲

Pingback: Everything You Know About Decentralisation is Wrong | Systemic Capital.com