Lucio Magri’s The Tailor of Ulm is a fascinating account of the history of the Italian Communist Party (PCI). He begins his account with an anecdote regarding the tailor of Ulm.

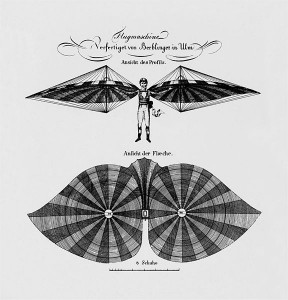

Ingrao, who had already fully explained his reasons for proposing a different course from that of the Party secretary, Achille Occhetto, replied in a jocular (though not too jocular) vein – by invoking Brecht’s apologia for the ‘Tailor of Ulm’, a German artisan who became obsessed with the idea of building a machine that would enable men to fly. One day, convinced that he had succeeded, the tailor took his device to the ruling bishop and said: ‘Look, I can fly!’ The ruler challenged him to prove it, but when he finally took to the air he crashed to the pavement below. And yet centuries later – Brecht concludes – human beings did learn to fly.

It is in this spirit of trying to understand why the PCI “crashed into the pavement below” that Magri begins his investigation. The book is imbued with a mixture of intransigent hope and a realistic sadness. The hope stems from his determination to keep the entire project from being written off without a careful critique which might be used by future socialists in coming to terms with our defeat. An account that can be used to know what was good along with what was bad. The sadness stems in the fact that all that remains of the project is the account of its demise.

This contrast is reflected in Magri’s personal life as well. Before completing the work Magri’s wife was diagnosed with cancer. Magri wanted to be euthanised with his wife, but she asked him to complete his book first, and so he waited until the work was completed before joining her. Some solace can be taken in the knowledge that his last gesture is a great gift to those of us trying to find a way that one day, we might learn to fly.

Magri is a clear partisan of a particular thread in the PCI, he is a centrist, in the Kautskian sense, by temper (though it’s doubtful he would self-identify), orientated to the left wing of the PCI by circumstance, and at once supportive of Lenin, the Bolsheviks, and the democratic road to socialism. These positions are somewhat contradictory and it is unusual for a consistent Leninism to put much stock in the capacity to realise socialism by democratic means. Indeed the PCI was full of many of these same contradictions and Magri lays them out in great detail. It’s clear that Magri is aware of the problems in reconciling Leninism with the democratic road.

As with the PCI, the source of Magri’s reconciliation of the tension between Lenin’s decidedly undemocratic practice and the quite different approach taken in Italy is Gramsci. Gramsci was the architect of a theory which allowed continuity with the Bolshevik strand while simultaneously describing the situation of Europe as requiring a different historical approach than was effected in the overthrow of aristocracy in Russia. This is perhaps most directly expressed by Gramsci as the difference between the war of manuoever and the war of position. According to Gramsci the European scenario required a more protracted combat on the fields of cultural hegemony and would not be possible by use of a direct smashing of the state by a sectional vanguard party.

The work however is valuable for more than just it’s exposition of the trajectory of the PCI. The methodology employed by Magri is exemplary. First, Magri is quite careful not to use betrayal as a cause of any of trajectories of degeneration or failure. The betrayal narrative is perhaps the most often used tool in the leftist toolbox being used to explain almost every failure in our glorious history of failures. It also has the quality of being singularly useless. It gives us no information about how to avoid problems in the future short of a determined moralism, which historically has never avoided defeat.

Second, Magri is very careful to situate the Italian political dynamic in the international context. It is literally impossible to understand the decisions made (such as the Salerno turn), and what pressures existed in the trajectory of the PCI without careful attention to WWII, the cold war and the political changes which occurred in the USSR. Magri carefully details these events and trajectories and their relationship with the PCI throughout the history of the party.

Magri is a Leninist, but not an uncritical one. Indeed he sees the germ of degeneration as being related to an over-centralisation of political analysis.

I have no wish to be silent about certain avoidable errors that could have been corrected when it was easy to do so, and that it is helpful, as well as just, to recognize today. The first error, to which Lenin himself paved the way, was an obsession with the ‘correct line’ in the centralized decision-making of the Third International, applied to tactical details in highly diverse situations; this led from the beginning to seriously flawed and inconsistent policies, such as the extremist course in Germany (for which Zinoviev and Radek were directly responsible) or the accommodation with the Kuomintang in China, until the moment when it began to massacre Communists.

There is some irony in the fact that uniformity of line is so often coupled with a tactical capriciousness which looks like wild fluctuation to outside observers. We can see these same sorts of spastic flailings in many of the small left formations that exist today.

The book also looks closely at the disintegration of the PCI concurrent with the unravelling of the USSR. Magri questions the usual narrative that the connection with Stalinism made such a dissolution inevitable. There are several reasons to take Magri’s thesis seriously. The first is that there are continuing left movements such as the PCF (in France) and Syriza and the KKE (in Greece) which have managed to salvage much more from their past in Euro-communism than the PCI did. The second is that the break with Stalinism had really already started in the 1950s and it was really quite complete by the time of the beginning of the 1980s. Further evidence in support is given in the detailed analysis of the PCI falling apart in the late 70s and early 80s which was concurrent with a global shift to the right with the rise of neo-liberalism, but preceded the collapse of the USSR, so the dissolution can not be straightforwardly causal.

The final chapter of the book is an excellent political analysis which Magri had written previously. It is still fresh and useful for our current situation as an exposition of the main epochal questions which we have to come to terms with on the left. These include the rise of productivity resulting in an historic oversupply of labour, a change in world demographics which mean that the expansion of capital geographically can not continue on too much longer and a stagnation of neo-liberal capitalism. It suggests useful approaches that the left might take to these problems and of getting beyond its own current stagnation. If you aren’t bothered to read the entire history of the PCI which Magri presents, I would still highly recommend reading the final chapter.

All in all, the book is highly recommended to anyone interested in learning about the history of Italian communist politics or anyone concerned with what we might take away from historical communist practice in Europe. The book is unfortunately ridiculously expensive. I suggest attempting to get your library to provide it if they do not already have a copy.