Martin McGuinness, Political Strategy and the Civil Rights Movement

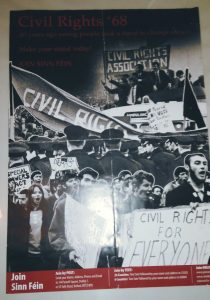

A Provisional Sinn Féin poster featuring Joe McCann and other Official IRA members (via Irish Political Ephemera)

The death of Martin McGuinness has inevitably prompted reflection on his career, with the reactions varying according to one’s political ideology. For the mainstream, McGuinness’s oeuvre is sharply divided into two halves, that of paramilitary godfather and political statesman, with the dichotomy arising from their view on the Provisional IRA’s (PIRA) long running campaign.

For Sinn Féin and a wider body of sympathisers, that division is an artificial construct; the two eras – military leader and peacemaker — are different forms of the same struggle. The change in strategy by no means entails an admission that the Provisionals’ military campaign was misconceived, only that it could no longer sustain progress towards their goal.

Interestingly, much of the online commentary sympathetic to Sinn Féin has revolved around how the Provisionals’ armed campaign was a fight for civil rights in Northern Ireland; the military campaign being an inevitable response to the brutality of British State and the loyalist mobs that the campaign’s progress elicited.

That narrative was summed up by Gerry Adams in his comment that “Martin McGuinness never went to war, the war came to him. It came to his streets, it came to his city, it came to his community.” McGuinness, having seen his community take a battering, took the decision to join the PIRA and hit back at the British forces. There is a lot of truth to this explanation, for undoubtedly hundreds and even thousands of people joined both wings of the IRA in these years, fuelled by such anger. But if the explanation is true, it is not the whole truth.

For the impression given by this explanation becoming the primary one for the long running PIRA campaign is that it was waged primarily for equality of civic rights. And while the violent response to the demand for civil rights was the fuel that drove many into the ranks of the IRAs, it was not the objective for which the PIRA fought for a quarter of a century.

Moreover, the very existence of the Official IRA (OIRA) when the conflagration was igniting, and who chose to go down a different path, illustrates that the long military campaign was not an unavoidable outcome, even after Bloody Sunday. This is not to traduce young men and women like McGuinness, whose reaction is understandable given the circumstances. But understanding their motivations does not remove the need for criticism. The question remains, were they, the PIRA, correct to respond militarily and for so long?

The question should be approached as one of strategy and goals, rather than one of just moral outrage. War is itself an outrage and once the guns are firing, atrocities abound. These are to be deplored and minimised, but they never settle the question of whether war is justified or not; that depends on the objectives of the campaign, the context, and whether greater evils can be prevented by recourse to military action now.

And that is a political question, requiring an analysis of the political possibilities and their potential at any given juncture. It is here that the weakness of the early Provisional movement is located. For, contrary to the modern playing up of their support for the northern civil rights movement, they chose instead to prioritise military conflict with the British State. This was not just a reaction to the loyalist mobs or the RUC. The PIRA were very clear that their goal was to force a British withdrawal through military force. The massive increase in recruits, as well as the weakening of the Stormont regime on foot of the civil rights disturbances created a relatively favourable context for waging that campaign; they were not the underlying reason for it.

Danny Morrison made this point in his review of Tommy McKearney’s book on the Provisional IRA:

“He suggests that the IRA by demanding a British withdrawal and an all-Ireland republic left itself no room for manoeuvre to contemplate an alternative to these stark objectives. Surely he appreciates that it was that goal which generated our passion and was what we were actually fighting and prepared to die for? And that during the fighting of a war to anticipate anything less than your sovereign demands is to undermine your struggle? He then confuses the current outcome of the struggle (the Belfast Agreement) as apparently having been the real objective: that the campaign was about reform and redressing the wrongs which the civil rights movement identified, rather than about ending partition and establishing a thirty-two-county socialist republic.”

In fact, it is striking that such a claim has to be defended at all. The persistent demand for British withdrawal, accompanied by a willingness to kill in support of it, was the dominant feature of the PIRA for the first 28 eight years of its existence. That the rights thesis is being promulgated illustrates primarily the cultural influence that Sinn Féin can today wield and thereby shape the narrative circulating, if not in the mainstream media, than at least amongst wider left-leaning circles.

To cap it all; the “Civil Rights First” strategy was the strategy of the Official IRA, not the PIRA, with the former being instrumental in organising the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association. If the founders of the PIRA had been of the same view, the other differences (e.g., abstentionism) would have been far less likely to result in them splitting off in the first place. Or at least, the inevitable split would have had all the force that O Brádaigh could muster in 1986, i.e., none. Of course, the OIRA, just like the PIRA, with its base in working class areas, got drawn into the vortex of military action. The difference was not that the OIRA were saintly choirboys or the Provos callous thugs, but in the strategic assessment of the respective leaderships. This saw the OIRA call a ceasefire, just as the killing was beginning to escalate in a big way.

In contrast, the Provisional leadership had a fundamentally different strategy, and it wasn’t one that revolved around the struggle for rights. In the words of Seán Mac Stiofain, the first Chief of Staff of the PIRA, their strategy was one of escalating the conflict by “moving from “area defence” to “combined defence and retaliation” and then a “third phase of launching an all-out offensive action against the British occupation system”. The latter phase involved a large-scale bombing campaign, which Mac Stiofain had borrowed from Greek Cypriots he had met in prison. Inevitably this led to a considerable civilian causalities, and a stoking of the already burning sectarian flames.

Absurd though it may seem to have to spell it out, the PIRA’s offensive phase, i.e., the bombings, was not dedicated to winning civil rights for nationalists, but to realising their core aim of British withdrawal. In his obituary to Mac Stiofain, Ruairi O Bradaigh, like Danny Morrison after him, was explicit about those aims:

“The three demands presented to British Ministers by his delegation in 1972 left no doubt as to what the IRA was fighting for: (1) The future of Ireland to be decided by the people of Ireland acting as a unit; (2) a British government Declaration of Intent to withdraw from Ireland by January 1975 and (3) the unconditional release of all political prisoners.”

The OIRA was certainly involved in area defence and retaliation too, even after their ceasefire was declared in 1972. The difference was that at a leadership level, the OIRA aimed to move the struggle from the terrain of military conflict and onto one of social struggle. Hence their general avoidance of bombings and their move to wind down operations. This took some time, and made some of their Volunteers unhappy, resulting in their eventual decamping to form the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA).

The Official leadership, primarily Cathal Goulding, Tomás Mac Giolla, and Seán Garland, with important backing from Billy McMillen, pushed for a civil rights campaign in the North as a way of cracking the Stormont regime, without provoking an intensely violent — and violently sectarian — conflict, which would in turn create the opening for building a class opposition — as opposed to an ethnic or sectarian one — to British imperialism. This was to be coupled with social agitation in the South as a way of building up a working class base in opposition to the compliant regime in Leinster House. Moreover, the Officials expanded their understanding of imperialism beyond the simplicity of London’s territorial control of the six counties to the impact that American capital, via the increasing levels of foreign investment, was beginning to have as well as the implications of EEC membership for Irish sovereignty.

The OIRA, then, prioritised the political and social struggle and therefore the leading role of a revolutionary working class party as the agent of that change. In the context of the early 1970s, this was a difficult strategy to pull off. The conflict entrenched sectarian divisions and stymied the Officials’ strategy in the North. Naturally, neither the British State nor the unionist paramilitaries as defenders of the status quo could be expected to play a progressive role.

The various strands of the republicanism, however, had the potential to play such a role, making the strategic choices they faced all the more important. The choice to engage in war had consequences, not only for hundreds of deaths and a deepening of the divisions, but of narrowing the space for political struggle. The argument from Gerry Adams that only later was it possible to engage in peaceful struggle for democratic rights misses the vital fact that the Official leadership had not only pushed for that in the crucial early years but had also argued, correctly, that a military campaign could not possibly achieve its political objectives; that to defeat imperialism required mass support; that socialism was the necessary modern incarnation of republicanism; that the working class was therefore the key social group to organise.

The subsequent trajectory of both the Officials and the Provisionals tells many tales. Usually this involves a myriad of anecdotes about the various sins of both groups through the 1970s and 1980s. More important, however, is their politics, then and now. Once the Provisionals abandoned their military campaign, they quickly evolved from revolutionary to constitutional nationalism. Not only that, in spite of considerable support from working people, they encased their nationalism in a near-Blairite centre-leftism: reductions in corporation tax, opening the New York Stock Exchange, speaking at rallies for billionaire Seán Quinn. No bridge is left uncrossed.

The Officials moved away from nationalism, embraced state socialism and built up a considerable working class base in the 1970s and 1980s but failed singularly to control their own Blairite cuckoos in Parliament — de Rossa, Gilmore et al. Even here, however, the difference is stark. Whereas the Provisional leadership — Adams, McGuinness, Kelly, MacDonald — are the Blairites, the leadership of the Officials, now named The Workers’ Party — Goulding, MacGiolla, and Garland — rejected the attempts by their protégées to shift the organisation away from socialism and into that bland centre, even at the cost of a massive reduction in size, from which it has thus far not recovered.

Historical context is necessary when appraising the choices of figures like Martin McGuinness. Demonisation as a simple terrorist does not persuade those who understand the context in which he made the choices. But criticism is necessary, particularly if we wish to avoid the romanticisation of a military campaign at the expense of political strategy. There were other options; there were even other revolutionary options. The Provisionals chose instead the traditional nationalist one, and settled into the role as Catholic Defenders with a republican gloss. As such, their present incarnation as modern day Daniel O’Connells is none too surprising.