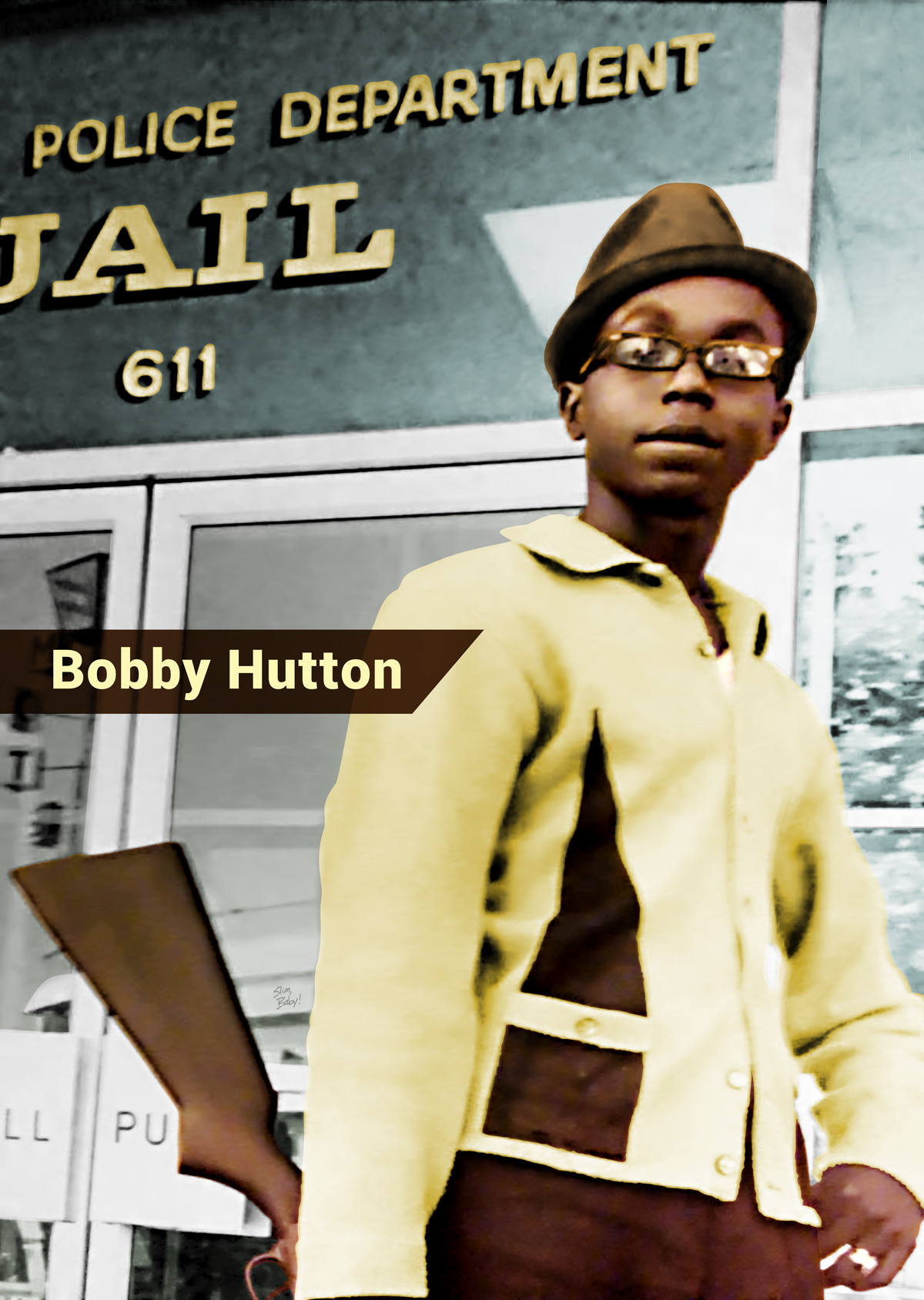

Bobby Hutton, killed in 1968 by the Oakland Police.

There are a number of strands that can be picked up from the recent, much-publicized events in Ferguson, Mo. Ferguson is a suburb on the innermost ring of St. Louis’s quite extensive “fat belt”, a European term for the series of developments and municipalities that co-exist, sometimes symbiotically, more often parasitically, with the larger cities they surround. Though the mass media has, as can be expected, been considering almost to the exclusion of all other questions the issue of Michael Brown’s race — a critical issue in the unfolding events, no doubt, but nothing new in the grand scheme of things in a long chronicle of police brutality and racially-instigated abuse of power by the privileged subclass designated to enforce the laws in the United States – it seems that more fundamental structural, institutional as well as cultural problems are unearthed, if one digs more than at the surface level of these events.

The particular circumstance of Ferguson and the city of St. Louis are a startling reminder of the racially tinged character of class relations in America. The lines between race and class in America are difficult to draw, and the country in many senses resembles Apartheid states and Israel1. This strange situation caused one radical academic to comment that “Under these circumstances… We can only say, … That [class analysis was] a true diagnosis of the situation in Europe in the middle of the 19th Century despite some of its logical difficulties. But it must be modified in the United States of America and especially so far as the Negro group is concerned. The Negro is exploited to a degree that means poverty, crime, delinquency and indigence. And that exploitation comes not from a black capitalistic class but from the white capitalists and equally from the white proletariat.” That individual was W.E.B. DuBois, founder of the NAACP, who also spoke of the “double consciousness” of blacks in America. DuBois might criticize the media picture today by questioning the very idea of attempting to find a “principal” point of entry into diagnosing the conditions of the black impoverished of Ferguson and elsewhere. These conditions are more than slightly complicated by inherent perceptions, prejudices and frictions between the races, even as regards their class differences (or similarities)2.

Ultimately, DuBois’s are empirical assertions that can be factuated or verified by the slightest interest in the historical situation of black St. Louisans. There is an excellent book by Colin Gordon on the subject3, and its findings are startling. For instance, Gordon points out the systematic nature of “white flight” in St. Louis, a phenomenon he shows actually pre-dated the Second World War, where many historians and the general public place it (with returning [white] veterans moving out of the city with their families into predominantly white suburbs like Levittown). In fact, the phenomenon goes back much further in St. Louis, with a zoning law in the early years of the 20th century banning the settling of blacks into predominantly white neighborhoods, and vice versa (although the former was the real issue of concern). Although this practice was later outlawed, implicit contracts were arranged between the realtors’ associations, which furthered this practice until well into the Civil Rights era. At that point it wasn’t permissible anymore. Some of the practices applied are appalling, including breaking down neighborhoods into smaller “sub-units” that could then more efficiently be segregated along racial lines, a useful tool when meeting with a reticent – or class conscious – citizenry.

Of course, this happened in other major American cities (Detroit, Baltimore, to name a few), and one might ask why all of this is relevant to the case of Michael Brown. Ultimately, fair housing legislation, like Title VIII of the 1968 Civil Rights Act signed into law by Lyndon Johnson banned even implicit discrimination with respect to housing, and we might say racial segregation is no longer an issue. However, a glance at any demographic map of most sizable American cities, including the beautifully rendered maps Gordon presents4, should suffice to convince the skeptical and show the damage had already been done. It should be clear to anyone that there is a strict racial dimension to these developments, in Ferguson and beyond.

The historically entrenched and economically perpetuated segregation of American cities raises a further concern. Physical separation creates the preconditions for institutionalizing learned (cultural) prejudices. It’s one thing when one’s children grow up in an ethnically diverse neighborhood where their friends, and even sometimes their relatives are of divergent ethnic backgrounds. It’s something completely different growing up in a neighborhood where, say, the cost of living (or a gate) prevents members of other ethnic communities from fraternizing. It’s also something different being schooled behind the high bars of equally inhibitive private schools, where ethnic homogeneity might be accompanied by religious and/or ideological homogeneity, a dangerous mix.

Countless studies have shown that “implicit racial bias” persist in the United States5. It is easy to imagine the influence one’s upbringing and environment have on such factors – and an equally strong argument can be made that this bias is not universal. Research to this effect has been conducted over many decades in many communities around the world. However, this is a stronger argument for eliminating the historically entrenched segregation in American cities. The death of Michael Brown, possibly at the hands of a racially prejudiced police officer, is sadly not a new phenomenon in the US. In fact, it may be a symptom of a society which without strong structural measures to integrate will continue to face crisis and disaster.

The reasons for this are clear: cultural biases become structurally institutionalized, and the Brown case is merely the latest example of this. There is also an economic dimension. The New York Times points out in a recent editorial that “[t]hings went off track… as the 21st century approached. The riots in Ferguson follow a period of setback for African-Americans, despite the fact that we have a sitting black president in the White House… Blacks suffered more than whites as a result of the 2008-9 financial meltdown and its aftermath, but the negative trends for African-Americans began before then.” The Times then points out that recent studies have shown that recent recessions have disproportionately impacted blacks. This should be a well-known fact to anyone with the least bit of curiosity about the racial divisions in the United States. In fact, the economist Dean Baker has been arguing this point for years, even before the financial crisis.

Another fact that is neglected with respect to the recent incident, and perhaps an associated point to the above, is that the argument that policies like the Voting Rights Act, Affirmative Action and EEO (Equal Employment Opportunity, also known as Title VII of the Civil Rights Act) are obsolete is clearly false. The fact that the Justice Department is conducting a civil rights investigation into the case of Michael Brown shows that, on an institutional level, there is still cause to treat blacks differently from whites. A near universal legal norm states that equality demands that “likes be treated as likes, and dislikes as dislikes”. A violation of either of these is commonly seen as being illegal and/or illegitimate. In fact, if Michael Brown had been a white, All-American, college-bound high school graduate in a white suburb, say, beyond Carondelet, on St. Louis’ extreme southern tip, the chances of the events occurring as they did would certainly be significantly less. This in itself is a reason for the existence of such institutions, given that institutional and structural racism is not a thing of the past, and black youths simply are not granted the same de facto rights as are white youths.

As a brief aside: there is something to speak of the militarization of the police force patrolling the city after the incident, but that’s also been the norm since 9/11/2001. However, the recent response to mostly peaceful protests is thankfully bringing national — and international — scrutiny to the issue. It’s one thing to have drones, automatic and semi-automatic weaponry and “explosive robots” in a war zone, where their utility at achieving the desired ends of defeating an armed enemy is unquestioned. It’s something completely else to use these weapons to “patrol”, “secure” and “police” Midwestern city streets, even if they are occupied by protesters demanding a more thorough handling of an extremely upsetting situation. That Holocaust survivors, state senators as well as a number of children – not to speak of journalists – have been gassed, harassed, injured and detained – often for hours – for exercising what appear to be increasingly less protected rights seems bizarre at first glance. When it’s placed into the wider context of the racially and economically divided situation in the United States, the picture becomes a lot clearer. As recently as the “Occupy Wall St.” movement, we saw the increasingly militarized quality of police tactics to pacify dissent. It seems merely that the situation in Ferguson is being handled by a less nuanced police force than the NYPD, and the police reaction is therefore much more exaggerated. The similarities are there, nonetheless.

One more incident begs mentioning, especially in light of the “second killing” in Ferguson. On April 6, 1968, two days after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, Eldridge Cleaver led a group of Panthers on an ambush of the Oakland Police. After a short shootout, accounts go, Cleaver and Bobby Hutton, a seventeen year old who was one of the youngest recruits to the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, attempted to surrender. Hutton apparently “stripped down to his underwear”, to show demonstrably he was unarmed. He was nevertheless shot twelve times, in an act one police officer who was present later referred to as “first degree murder”.

Michael Brown’s case is much more damning for the officer involved than that of Hutton, who, if accounts of the attempted surrender are true, should nevertheless never have been shot. If anything is clear from viewing both incidents on a historical continuum including the Watts riots, the riots following MLK’s death, the Rodney King riots and other similar incidents over the years (including in Cincinnati in 2001), then it should be clear that the tasks of the Civil Rights Movement are not over. King himself became more closely associated with the Poor People’s Movement in his last years of life, and saw the inextricable ties between class and race in America. They appear as two simultaneous and related, but different problems, both requiring concerted effort to create the pressure sufficient to change circumstances for the more harmonious. Creating measures to disincentivize further suburban sprawl – and thus reducing the racial and class-based stratification of the country – are a start, as are more strongly promoting Affirmative Action and similar programs on a federal level. More creative measures to curb urban decline and de-industrialization (which fuel joblessness and deprivation, particularly among racial minorities) should also be considered.

Before Michael Brown it was Trayvon Martin, and before him a long list of others, including Emmett Till and the four Mississippi civil rights workers killed by the Ku Klux Klan in 1964. Like gun control, it’s an issue that will keep resurfacing until enough pressure is exerted to address the fundamental issue.

1. For instance, see the groundbreaking work by Douglas Massey and Nancy A. Denton↩

2. For a parallel discussion of DuBois’s point, see, for instance, Max Blumenthal’s analysis of the Mizrahim in Goliath, themselves an underclass, who are coerced into pushing their anger at the Arabs, still below them.↩

3. Mapping Decline: St. Louis and the American City. Princeton University Press↩

4. Gordon’s maps are available online (here and here) and reveal a very interesting, if turbulent and at times nebulous history of the city once hailed as the “Gateway to the West”. Gordon’s book points out several other idyosyncracies that helped to strangle St. Louis proper after the majority of its white populace had either crossed state lines or settled into the ever expanding rings surrounding the city, like the policy of home rule and the advantages it creates for suburbs. I won’t go into that here.↩

5. Including this relatively recent study by the National Institute of Health http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2555431/↩