A socialist Labour Party government has finally come to power in Britain. Harry Perkins, a third generation communist, wins the position of Prime Minister. He and his cabinet immediately embark on a programme to break up media monopolies, nationalise industry, declare military neutrality and make radical steps towards government transparency. Civil society is sent into a tumult as the media lambasts his government and industry and the secret state colludes to ensure that no serious changes in the social order take place.

A socialist Labour Party government has finally come to power in Britain. Harry Perkins, a third generation communist, wins the position of Prime Minister. He and his cabinet immediately embark on a programme to break up media monopolies, nationalise industry, declare military neutrality and make radical steps towards government transparency. Civil society is sent into a tumult as the media lambasts his government and industry and the secret state colludes to ensure that no serious changes in the social order take place.

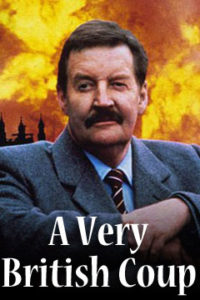

So starts the 1988 TV drama, A Very British Coup. The film is based on an earlier novel written in 1982 by Chris Mullen, himself later a labour MP. The character of Harry Perkins appears to be loosely based on Tony Benn, who contested the labour leadership in 1976. The core idea of the film is probably best summed up in Tony Benn’s own words:

As a minister, I experienced the power of industrialists and bankers to get their way by use of the crudest form of economic pressure, even blackmail, against a Labour Government. Compared to this, the pressure brought to bear in industrial disputes is minuscule. This power was revealed even more clearly in 1976 when the IMF secured cuts in our public expenditure. These lessons led me to the conclusion that the UK is only superficially governed by MPs and the voters who elect them. Parliamentary democracy is, in truth, little more than a means of securing a periodical change in the management team, which is then allowed to preside over a system that remains in essence intact. If the British people were ever to ask themselves what power they truly enjoyed under our political system they would be amazed to discover how little it is, and some new Chartist agitation might be born and might quickly gather momentum.

The pervasive paranoia of the film is its great genius. There are no car chases, no explosions and no shootings and yet there is a palpable tension–a fear of impending doom, of forces vastly larger than what is visible working in the background. The faces exchanged as Perkins looks in at the help as he enters Downing street relay to us the message: We do not know who is on whose side. The dangers lurking in secret are far more frightening, realistic and compelling than the intrigue in any Bond film. I found myself filled with rage at the actions that the enemies of democratic rule were willing to take to subvert it.

However, all is not despair, a former flame of Perkins, holding a copy of The Ragged-Trousered Philanthropist, serves as a motif of hope and love, reminding us what motivates the protagonists to endure such shoddy and stressful treatment with only slim hopes of success. Interestingly, Tony Benn recently wrote an article entitled An Antidote to Socialist Despair, exploring the relevance of the book to our current context.

The extent to which the Perkins’ government is prepared to go to overcome blackmail by international finance is substantial. They do so by making a deal with Moscow in order to sideline the IMF and finally obtain the funding necessary for their programme, a delicate move that could only have been made in a multi-polar system which unfortunately we no longer have. This move, coupled with the insistence of removal of US military bases from the UK, leads the CIA to become involved in coordination with the UK secret state to depose Harry.

The attention paid by the drama to collusion between the secret state, industrialists and the media was unusual as it is often understated by the left. The left tends not to want to get lumped together with mad conspiracy theorists and in doing so often errs too far on the side of credulity. The fact of state collusion with industry and the intransigent attempts to cover it up have just recently resurfaced in the refusal to release documents relating to the Shrewsbury 24.

Any attempt to take a democratic road to socialism needs to seriously assess how it can deal with the secret state. MI5, MI6 and the CIA are not something that is easily controlled or easily eliminated, they have their own agendas and are often quite willing to work with finance and industry in order to keep democracy in check. Decommissioning these actors will be very difficult to say the least.

The film is excellent drama and while the socialist Programme which is acted out is perhaps not the most enlightened of socialist programmes for government it is probably quite realistic in terms of the limitations of acting through the state. The moves to nationalise do include provisions for workers democracy and the agreements are made through the unions rather than via state dictate, which is certainly more progressive than many visions of nationalisation (see Connolly’s excellent short essay on the subject 1). The limitations of simply dividing up media monopolies should be pretty obvious. Further, the dismantling of the nuclear weapons unilaterally seemed pretty pointless, though perhaps it could be used to reinforce the demonstration of neutrality. There are many other provisions that I would suggest to the Harry Perkins government if I had the means to do so. Unfortunately it’s too optimistic at this stage to imagine any short term prospect of a socialist government in power in a European country. Further, the problem of finance is even more acute than it would have been for Perkins in his fictional time-line. What was true for Tony Benn in the 1970s is even more true now.

All in all, I think the film is a must see for socialists and I highly recommend it.

- James Connolly, href=”http://www.marxists.org/archive/connolly/1901/evangel/stmonsoc.htm”>State Monopoly versus Socialism ▲