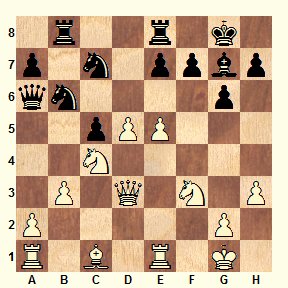

A hypermodern position arising from the Benko Gambit

Aron Nimzowitsch was a brilliant chess theorist who broke new ground in the 1920s with his treatise: My System. The system he proposed has become the most famous exposition of what is known as the Hypermodern school.

Positional play, the notion that there are important long term strategic ramifications to the current static conditions of the board was then a relatively recent development. Basically, the idea is that the static features determine what kind of tactics become available, and that fortune would favour the astute positionalist with excellent tactical opportunities. The school was practically founded by Willhelm Steinitz in the late 1800s, but was promoted in a very formulaic way by his acolyte Tarrasch.

Nimzowitch took the principles of positional play very seriously, but decided to develop them in a radically new fashion. The core of his idea was to allow the opponent to take the centre – during this time, behind the lines, black would focus long range and mobile attacks on whites weaknesses. When the centre overextended itself, the positional collapse could be rapidly overtaken. It was time to rush in with mobile forces to deal decisive blows.

Chess is in fact a highly assymetric sport, even though this asymmetry appears quite subtle to the novice player. The hypermodern approach, it turns out, suits black better than white. The reason for this is that black simply does not have time to conclusively take the centre, and so must content itself with either contesting from a point of weakness, or hoping to find a more clever way to force hyper-extension of whites forces.

Politically, the vast majority of the population can be said to occupy a position that suits itself to a hypermodern approach. The centre is quite obviously occupied, so a rush for space is simply not possible. In this way we can see an interesting parallel between ideas from the hypermodern school of chess and Gramsci’s notion of the war of manoeuvre versus the war of position – ideas themselves borrowed in analogy from Carl von Clausewitz treatise on warfare.

Since space is already filled, there can be no rush to fill it up. Instead mobility must be subtle, and it must occur behind the lines of a positional orientation. Long term vision means setting up the terrain to ensure that tactical possibilities will open up later.

This analogy can also bring insights when we view revolution through its lens. Revolutions are essentially events in which the centre collapses. However, this centre never collapses simply from the full scale assault from the fringe; no revolution in modern history has been so. Instead, the centre has to have its forces in a complete disarray, and in this disorientation, well placed forces are able to displace the centre.

The Russian revolution gives us a very good example of such a situation. The Tsar was in a war which was leading to horrible losses. The economy was in very serious trouble and every report of new losses at the front caused a decay in the moral support of the troops who would soon be marched out to the front. Only at the point that the military personnel were completely uninterested in following orders, and many sections were threatening direct revolt with or without the Bolsheviks, did a revolution occur.

Since the proletariat is playing without the centre, and generally with quite meagre forces – materially much weaker – any sort of revolutionist approach is suicidal or impossible. Generally it is simply impossible because most people are not up for suicide.

The population does not make revolutionary situations. Instead, this role must fall to the ruling class. They must become disorganised, over-extend from the centre, blunder, and leave quite terrible weaknesses which can be taken advantage of.

This does not, however, mean actionless waiting for us. Our task is to attempt to set up the terrain to suit ourselves. It is to set up the terrain to allow mobility behind the lines. It is to set up permanent bases of power which can be utilised tactically when openings exist. It means attempting to encourage the hyper-extension of power that weakens the centre. In short, we have our work cut out for us.

5 Responses to Hypermodern Political Strategy