The European Left Summer University was held between July 3rd and 6th. Organised by Bloco de Esquerda of Portugal, the University was a three-day series of lectures and seminars on the key issues facing the European Left, the party of parties that includes SYRIZA (Greece), Front de Gauche (France), Izquierda Unida (Spain) and Die Linke (Germany). These parties are themselves coalitions, with Communist Parties often occupying a leadership role within them.

(We also took notes on the sessions at ELSU)

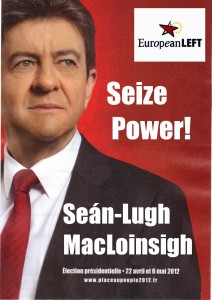

Predictably, the crisis occupied centre-stage in this discussion, and lectures from Mariana Mortagua on European monetary policy and Jean-Luc Melenchon on the strategic choices for the Left were a particular highlight. But topics such as ‘Political Communication techniques’, ‘Agricultural and Industrial Reform’ and ‘Universal Free Transport’ showed the high level of practical work and political development in the individual parties and the network as a whole. About half of the time in sessions was turned over to debate, allowing for contributions from the floor. Both speakers and contributors were live-translated into Portuguese, French and English, so we monoglots were able to chip in occasionally.

Coming from the bedraggled Irish left, we found the event inspiring and provocative. The sessions and informal conversation showed that broad socialist parties are possible, that they can be coherent while accepting differences of opinion and they can develop analysis and policy to deal with the current situation and articulate a realistic path forward. There was no magical thinking that saw revolution lurking around every corner nor a resigned opportunism that only hoped for mild ameliorations. Instead, there was a clear belief in the need for a socialist Europe and a desire to address the current crisis and lay the path for further advances. People talked openly about political differences and the difficult questions posed by success; for instance, the Finnish Left Alliance joined an uncomfortable coalition with rightwing parties in order to keep the quasi-fascist True Finns out of power while Izquierda Unida must deal with European Commission efforts to kibosh their law to turn unoccupied housing over to the homeless in Andalusia.

The broadest identifiable divide between the parties tended to be between the old Communist Parties of the Mediterranean and their Nordic counterparts, with the latter exhibiting a markedly less Marxist tinge to their contributions. Exhibit A was Die Linke’s proclivity for analyzing the Middle Eastern situation from an almost purely moral viewpoint, whether from a pacifist stance or a ‘support the people’ one.

Worthy though moral sentiment may be, it is no substitute for an understanding of the structural dynamics at work, a comprehension in evidence from the rather more cynical analysis of the French and Spanish Communists who identified the recent Snowden revelations as an open admission of the subservience of the European countries to the United States and warned that the forthcoming Atlantic free-trade agreement is likely to have serious implications for the Europe’s capacity to escape American tutelage in the foreseeable future.

The cleavage between the Greeks and the Latins on the one hand and the Nordics on the other also bubbled up in regard to their attitude to the dynamics of European unity itself. As is well known, the Communist Parties opposed the EU Constitution so I had expected a more skeptical attitude, from the French in particular. However, scathing though they were at times, they missed no opportunity to emphasize that taking on capitalism required more unity at a European level, albeit on a new basis. In contrast the Scandinavians and at least some of the Germans indicated a preference for breaking up the Euro and returning to a situation of more national independence.

SYRIZA, in particular, were having none of this, and clearly hold no illusions about their fate if condemned to national isolation. The difference between the north and the south perhaps emanates from the relative immunity of the northern countries to neo-liberalism. They have both happy memories of the welfare state, which seems eminently salvageable on the national level. The pressure of the crisis on the Mediterranean parties, meanwhile, has forced them to analyse their situation at a deeper level. That said, there are no doubt divergences of opinion within each of the constituent parties as well as between them.

The vast majority of the participants in the university were coming from one of the constituent parties. This put us in a rather odd situation of having to introduce ourselves as being relatively unaffiliated. Virtually every time the question came up, people would ask why were not in Sinn Féin. Many people at the summer school were involved in the EU parliament and knew Sinn Féin through their involvement in the GUE/NGL. Sinn Féin have very effectively positioned themselves as the only left in Ireland in the international sphere. It was somewhat difficult to respond to the query without coming off as unnecessarily sectarian. Perhaps the best answer to “Why aren’t you in Sinn Féin” is “Why isn’t Sinn Féin in the European Left”?

The atmosphere was cordial and congenial amid debate and disagreement. The evenings of drinking and conversation enabled informal chat and debate, with English being the lingua franca of the gathering. When people could not communicate directly, there was a shared repertoire of songs like the Internationale and Bella Ciao. Perhaps most impressive however was the sense of ambition. The attendees hope for major transformation and they’re trying to figure out how to accomplish it. Back in Ireland we might not have any party of such scale or ambition, but we can try to emulate that sense of vision and the seriousness and dedication it calls for.

Pingback: European Left Summer University | Look Left | S...