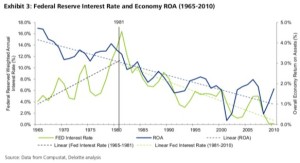

A few years back Deloitte issued a report1 that had a long term analysis of the rate of return on various measure, investment capital, equity and assets. In all three cases there was a fairly clear downward trend. Deloitte come up with some tentative descriptions for the cause of this which I will not deal with here other than to say they are, in my opinion, extremely dubious. Their theory boils down to the idea that individual capitalist have just not exhibited good management skills.

A few years back Deloitte issued a report1 that had a long term analysis of the rate of return on various measure, investment capital, equity and assets. In all three cases there was a fairly clear downward trend. Deloitte come up with some tentative descriptions for the cause of this which I will not deal with here other than to say they are, in my opinion, extremely dubious. Their theory boils down to the idea that individual capitalist have just not exhibited good management skills.

Now, Marxists have been talking about the tendency for the rate of profit to fall (TRPF, TFRP, LTRPF and probably six other permutations in the literature) for donkey’s years. The manifestations of this argument have taken many forms over many years, and have ranged from a tendential occurrence to an absolute law – from a cyclic event, to something which exists over all time. Those who are interested in crisis theory general push the former: they see it as a factor which helps to cause cyclic crises. Further, there are quite a few that are in the middle.

Recently there has been a big spat between Heinrich (who we have talked about elsewhere) and Kliman et. al. on the question. I don’t want to weight in directly on their argument, but I’d like to shed some light on the subject in general.

First, it should be pointed out that Marxists didn’t even formulate the original argument, in fact the original idea owes to none other than the eminent classical political economists Adam Smith.

The argument is essentially game theoretic, though game theory had not yet been invented at the time. In fact, the entire sensibility of the Labour Theory of Value rests on arguments which require a number of competing agents in order to make any sense at all. Erik Olin Wright proposes perhaps the simplest description:

each individual capitalist, in order to maximize profits in the face of competition makes technical innovations in the forces of production which increase the organic composition of capital (roughly capital intensity). This is rational for each individual capitalist: they are just maximizing their individual profits. But the aggregate effect of this is to undermine the conditions for the on-going production of profits. If capitalists could cooperate and quell competition and prevent the rising organic composition of capital, this tendency could be halted, but the laws of motion of capitalism – i.e. the drive for accumulation under conditions of capitalist competition – make this impossible.

This argument has been widely believed over long periods of time. In fact, George Orwell used the idea as the basis for some of the dynamics in 1984.

However, there are a number of complications with this most basic argument. I will ignore the other countervailing tendencies for now and focus on one, capital intensity, but if you want to read about some others see2. Capital intensity, the amount of productive equipment in a given productive endeavour, is only very roughly related to the value composition of capital. The value composition of capital is generally defined as c/v where c denotes the “constant capital” inputs, and v denotes variable capital, or the value contribution from (living) wage labour.

We will take a simple schematic example which imagines that a certain value of our machine capital is used up in production. Take the following simple schematic example:

A widget producer produces one widget using a robot and a worker. The robot usage cost is €10 (initial capital costs amortised plus depreciation) the human cost in wages per widget is €10.

Improvements in robot design lead to a decreased cost of robots to €3. Human wage rate remains steady, hence the widget producer employs 3 robots.

Assuming that value is a good predictor of price, we have a situation in which the technical composition of capital (TCC) in terms of actual raw machinery employed relative labour has tripled, but the value composition of capital (VCC), that is, the capital employed in value terms relative worker labour, has actually decreased.

Uneven and combined development

Significant contributions have also been made by David Harris3. The idea that the TCC and OCC are not identical is clearly outlined in this piece and Harris lays out a sketch of an argument about what we might want to look at to see a more fundamental cause for the tendency than the OCC.

The original OCC argument is very straightforward, and the empirical evidence supports such an actual tendency in production, so is there a link between the TCC and the OCC?

Harris’ work is where we can look for a clue. His novel use of “uneven and combined development” (a concept suggested by Trotsky) allows us to peer into what might be behind the apparent empirical linkage.

Firstly, Harris, following Marx, points out that there are two departments, production of the means of production (Department I), and production for consumption (Department II). These two departments have to be distinguished: as to ensure that the OCC gets smaller means we need a suitable investment in Dept I.

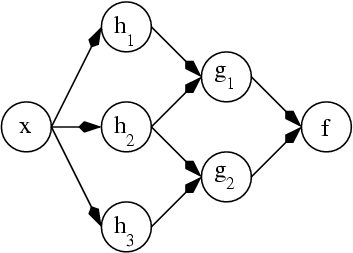

Yet as Harris also points out, the internal structure of Dept I is an hierarchical dependency graph (or a matrix). This means that there are various regions in which uneven capitalisation might manifest changes in the OCC. For one, application of investments in these areas may not in fact yield immediate super-profits. Time lags (due to the generally expensive nature of much MOP) and bottle-necks in the dependency graph make it less obvious where investments can occur. The anarchic nature of capital makes it hard to coordinate these carefully.

Yet as Harris also points out, the internal structure of Dept I is an hierarchical dependency graph (or a matrix). This means that there are various regions in which uneven capitalisation might manifest changes in the OCC. For one, application of investments in these areas may not in fact yield immediate super-profits. Time lags (due to the generally expensive nature of much MOP) and bottle-necks in the dependency graph make it less obvious where investments can occur. The anarchic nature of capital makes it hard to coordinate these carefully.

Capitalists find it straightforward, if difficult, to realise super-profits in Dept II production, since the introduction of capitalisation causes an immediate acquisition of money from consumption. Further, most humans do not consume MOP directly, so they are more likely to think about investing in Dept II just because they are humans. This bias could lead to problems of profitability.

Further, if the dependency graph has no cycles (is a directed acyclic graph or DAG) then we can always recover the original argument by simply going to the top part of the chain. Eventually capitalisation here will lead to a fall in the average rate of profit.

It’s not possible to insist that the dependency graph be a DAG for real production. There are some MOP input goods which will cause a decrease in cost for the production of MOP across the board – goods which represent cycles of dependency. Energy and infrastructure are of this form. For instance, in the production of oil we can reduce the costs if oil falls in price. This will potentially lead to non-linearities. Despite this, if we use a temporal interpretation of production, where prices in the last cycle are not directly fixing prices in the next cycle, it seems that even these cycles may not allow an escape from the law.

Fragmentation – Diversification

These laws imagine a fairly fixed group of commodities. In the real world new commodities are coming up all the time. This means that competition in new areas are presented, old commodities cease being used and the potential for a new higher profit comes into play due to the need to start the capitalisation game all over again.

This potential route of escape has a few problems with it however. Our development of the means of production has become increasingly flexible – robots are now able to make several different kinds of car for instance, and when new cars are introduced the assembly line has to change, but in less ways than in the past. As this flexibilisation of capital increases this countervaling force will likely decrease as well.

The Worker

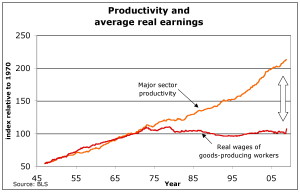

There are other ways of course that profits can be realised. The constant increase in productivity of workers means that one worker hour is now producing more physical stuff. That may mean that wages can see a continual decline in the share of value without leading to real diminution of living standards for workers. Marx suggested that the expulsion of labour from production due to capitalisation could create a reserve pool of labour that could assist in this cycle. Indeed, there is evidence that this factor is in play in many countries where real wages have stagnated yet capital has been getting ever increasing portions of the pie. From the evidence it seems that perhaps even this stagnation is not enough to save profits.

There are other ways of course that profits can be realised. The constant increase in productivity of workers means that one worker hour is now producing more physical stuff. That may mean that wages can see a continual decline in the share of value without leading to real diminution of living standards for workers. Marx suggested that the expulsion of labour from production due to capitalisation could create a reserve pool of labour that could assist in this cycle. Indeed, there is evidence that this factor is in play in many countries where real wages have stagnated yet capital has been getting ever increasing portions of the pie. From the evidence it seems that perhaps even this stagnation is not enough to save profits.

Forwards!

This is all well and good, but why should we care? Some are opposed to the TRPF as they claim that it makes it look like capitalism will simply go into decline of its own accord and that we can just sit on our hands and wait. I find this argument uncompelling for two reasons. Reality does not care whether or not you sit on your hands and wait. Whether or not the tendency exists is irrespective of what you think people should do. The TRPF either tends to hold or it does not.

However, the second and perhaps more important is that the inexorable decline of capitalism does not mean the incline of socialism. Though the vast forces of production that exist now give us the potential for socialism, they do not in themselves create it. To socialise the means of production means finding concrete organisational and technical methodologies for bringing production into the service of the broad masses of the people, rather than having production controlled entirely by the profit motive. It requires us to bring about a democratic and human focused approach to investment in society. This will not spontaneously appear simply because capitalism is entering into stagnation.

All sorts of dystopian futures can be imagined that do not require that capitalism finds a natural way back to profitability. Perhaps the capitalists will make androids for themselves, completely expel labour from production and simply leave the rest of us to die in unemployment. Perhaps we entered into some period of highly productive feudalism. Perhaps social instability from inequality gets so intense that the means of production are destroyed and we start over at a new higher profit rate. Perhaps ways of suppressing wages even more intensely are developed.

Our best hope for avoiding these futures is to find routes by which we can push society towards a cooperative system of production.

- href=”http://www.deloitte.com/view/en_US/us/Industries/technology/center-for-edge-tech/b79e86a8b1363310VgnVCM2000001b56f00aRCRD.htm”>The Long-Term Decline in Performance is a Result of Firm’s Slow Response to The Big Shift, Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, 2012 ▲

- href=”http://www.academia.edu/1078138/From_Adam_Smith_to_the_dynamics_of_the_profit_rate”>From Adam Smith to the dynamics of the profit rate, Cockshott, Zachariah, Tajaddinov 2010 ▲

- href=”http://www.stanford.edu/~dharris/papers/The%20Organic%20Composition%20of%20Capital%20&%20Capitalist%20Development.pdf”>The Organic Composition of capital, David Harris, 1985 ▲