When we are born we see the world without preconceptions. The sense data from the world flows into our brains without systematic categorisation.

For this reason the world seems a nonsense. We can not understand it and we can hardly move properly. Only the most critical system functions, such as breathing and eating, are organised by a more primitive instinctive part of the brain.

Later we learn to take specific sense data and to abstract it, to form generalities, to find objects that repeat themselves and to find what manner of active control we can exert on the world.

An adult human has very sophisticated theories of the world. They have models in their minds of people, places, objects, possibilities of action, and methods of communication.

Much of the structure of these theories is formed not simply by the individual, but is the result of communication. Humans engage in a collective social process of formulating understandings of the world, of themselves, of social roles, of collective activity, and of how individuals should fit into it.

Physics was the culmination of a social process which organised a programme to study the natural world and to understand its regularities. It was a collective activity which found generalisations which could be applied to organise and make sense of the world from what would otherwise be disorganised, and therefore less useful information. For instance, collections of facts about heat do not in themselves constitute a theory of thermodynamics. That requires systematic abstraction.

Historical materialism is a similar programme, but with a the aim of understanding history. It is an attempt to make sense of human social processes themselves and analyse them to form coherent theories. Historical materialism is not itself a theory. Rather it is a project with the aim of understanding better how history unfolds. Under its aegis we hope to find for humans theories of process and theories of trajectories.

Attempts to find regularity in the trajectories of human society go back to ancient times. Early attempts at astrology had yielded tremendously useful understanding of when floods would occur and there were hopes that it could yield a theory of victory in battle.

The modern programme is however best known because of the works of Marx and Engels. Marx was not the first to attempt to produce a scientific theory of history. Saint-Simon and his student Comte had also begun an investigation into what dynamical principles could be used to understand the course of history. However, the theory developed by Marx, Engels, Plekhanov, Kautsky and many others is particularly notable in the range of periods and subjects which were looked at through its lens and how productive it has been as a programme. Materialist accounts of everything from the family and Christianity to the French Revolution have been produced, yielding deep insights and even important predictions.

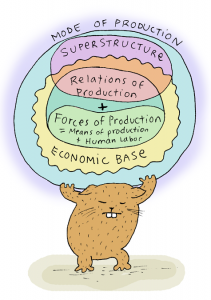

Marx put forward some theoretical descriptions of how we should view human societies as contingent on definite physical constraints which are placed upon them by their context.

In the social production of their existence, men inevitably enter into definite relations, which are independent of their will, namely relations of production appropriate to a given stage in the development of their material forces of production. The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.

Marx — A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy

Many have complained that historical materialism, and especially the theory given above, is too deterministic; that it doesn’t give any space for agency. However, one may as well make the same complaint about our physical theories for all the good it will do. Railing against the organisation of physical laws will hardly provide you with greater space for agency. The question is whether it is accurate rather than whether it makes you feel completed as a human being.

Despite the irrelevance of the complaint, I believe it is still possible to have agency within historical materialism, just as it is within physical theories. Just as a child becomes more capable of motion after producing a theory of their surroundings, so to should socialists be more capable with a firm understanding of the social terrain. Clearly Marx believed similarly or he would not be so well know for the passage: “Philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it”, a very active sentiment indeed.

The General and the Particular

Historical materialism seeks to understand history in the broad sense. But in order to do so, much as in physics, it is often useful to apply the general framework to the study of dynamics of more specific periods and processes within it.

Marx’s critique of political economy given by Marx in Das Kapital can be viewed as a materialist analysis of a particular spacio-temporal extent and the dynamics which occur in that context. It starts from the position of classical political economy, and especially the Labour Theory of Value (LTV) and extends and amends it with powerful new insights.

The Labour theory of value was first articulated by Adam Smith in “An Inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations”. While Smith recognised that labour was systematically disadvantaged in negotiations over wages unless they combined, he did not develop a theory of exploitation. Among the first to recognise that the labour theory might imply that workers were systematically exploited was Tomas Hogdskin who laid out his argument in “Labour Defended against the Claims of Capital” in 1825.

The Labour theory of value was first articulated by Adam Smith in “An Inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations”. While Smith recognised that labour was systematically disadvantaged in negotiations over wages unless they combined, he did not develop a theory of exploitation. Among the first to recognise that the labour theory might imply that workers were systematically exploited was Tomas Hogdskin who laid out his argument in “Labour Defended against the Claims of Capital” in 1825.

The LTV posits that in the main, production yields prices which are closely related to the labour of wage workers which it took to produce them1. Under capitalism the relations of production are set up such that commodities trade at a price related to the labour embodied in them and the capitalist takes some of the labour value as surplus and the wage worker gets some of the remainder in order to reproduce themselves.

Some of course will note that this does not account for all costs to society or all labour which is expended in society. The costs of pollution are never present in the price of a product. Some inputs, such as Nitrogen, are natural resources which require no direct labour to obtain. We breath air, a vital object of consumption without ever paying for it (yet!) Neither is any support labour, such as domestic labour which is necessary in the reproduction of the labourer included. However, this is not a fault of the theory which explains the workings of capitalism and how prices arise under capitalism, but a fault of the social arrangements of production which yield the theory to be true.

The theory of the LTV, and indeed the critique of the social arrangements which give rise to the society of production for exchange describes the important factors in our current arrangement of the activities and capacities, and most importantly, the social organisation of labour of humans.

Social organisation of labour is the trans-historical fact of human existence. It exists in hunter gatherer neolithic societies and it will exist under socialism. Just as Capital describes the social organisation of a particular society, in general historical materialism revolves around how we, using our minds and our bodies, interact socially to reproduce ourselves as a society. It is the institutions that we organise ourselves into, coupled with our environment (including the forces of production which are currently extant) and the way that these social institutions organise labour that give rise to a mode of production.

Selection and Reproduction

In 1859, Darwin published “On the Origin of the Species”. This work presented a mechanism by which evolution and speciation could take place without making reference to any “guiding hand”. The general framework presented by Darwin, including the ideas of selection and propagation are among the most momentous developments in the sciences.

In 1859, Darwin published “On the Origin of the Species”. This work presented a mechanism by which evolution and speciation could take place without making reference to any “guiding hand”. The general framework presented by Darwin, including the ideas of selection and propagation are among the most momentous developments in the sciences.

Marx recognised quickly the importance of Darwin’s theory and immediately began looking at how to apply it to political economy and historical dynamics.

Darwin’s work is most important and suits my purpose in that it provides a basis in natural science for the historical class struggle.

Marx, 16 January 1861

Marx is most famous for his work, Capital, a magnum opus that has made him the most cited scholar in history. Yet one of the strongest contributions of this work was to finally give a plausible mechanism for Smith’s invisible hand by presenting a selectionist view of capitalist competition.

Each individual capitalist could only continue to survive as a capitalist by investing in productive activities which could obtain profits. Viewing the entire system of production and consumption and the circuit of capital as an ecosystem helps to explain why commodities will tend to sell close to their labour value. Similar arguments using a selectionist dynamic drive suggest the tendency of the rate of profit to fall.

So it is precisely the pressures on capitalists, and their need to reproduce themselves, in this case to obtain sufficient profit to remain capitalists, which gives the dynamical drive to capitalism. The merger with Darwin’s selectionism finally gives a causal view of how history can unfold.

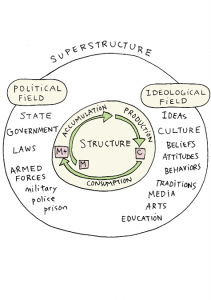

In contrast to the view of a simple determinant primary factor, or hierarchy of factors, we are invited to take a metabolic conception of the dynamics of history. This system in its totality has various interlocking and co-developing features.

Base and Superstructure

Social organisation is not entirely without constraints. Since society must reproduce itself, only those social arrangements which can exist will continue to do so (it is a tautology!).

Humans have a great deal of reflective capacity. We sometimes contemplate what we are doing not just how we will do it. The social relationships that we form with others change, and our culture changes over time. We build up stories about why we do what we do. Sometimes these are critiques, but more often than not they are justifications.

While there are aspects of culture that move very rapidly, there are also social conventions which move more slowly and can be seen to be very conservative. The elements of society which tend to be most conservative are those which relate directly to the economic – the elements of society which are literally necessary for its own reproduction. The social convention of money is vastly less likely to change next year than the spring fashion collection.

While progressives often find such conservatism with respect to social change frustrating, it is in fact adaptive. If our mechanisms of social reproduction were too plastic, we would find ourselves unable to engage in large scale cooperation. The ability of humans to adopt a set of cultural norms allows us to create societies on scales far larger than the scale of those we know and trust directly.

There is an institutional and cultural base which is closely involved with the reproduction of society. It forms a sort of critical infrastructure, without which we would be in danger of catastrophic failure.

On top of this there is a more fluid, plastic and more rapidly evolving aspect of society. Since humans possess critical faculties they need to have more than just a description of what must be done. They have to understand why it must be done. The superstructure provides many of the justifications and defences of the importance of the base. It is largely (though not completely) the theorisation, or theology (if you will) of the current organisation of society.

However, the superstructure, being more fluid and rapidly evolving, due to the critical faculties of humans, is not rigidly constructed to reproduce the base. Some of the variation will be of the kind that is irrelevant to the reproduction of society, such as whether grunge or dubstep is in fashion.

Various interpretations within historical materialism have focused on understanding the relationship of superstructure and base. In order to understand the relationship it’s important that we understand it as a process evolving in time.

There are several static pictures which give rise to a distorted view of the relationship. The first is economism, which sees a causal arrow from the base to the superstructure. This vulgar Marxist view of the determination of the superstructure entirely from the base leaves us unable to explain developments of the base itself. This view leaves no possibility for change from the development of politics.

The second common view on the relationship is what I term “culturalism” which sees the superstructure as determining the base. This view posits an almost unbounded capacity for humans to reconfigure every aspect of society based on ideas.

The third sees a bidirectionality between superstructure and base. As a static picture it is closest to correct, however the manner in which the two can effect change is obscured by questions of primacy of cause. It evokes the old question: “Which came first, the chicken or the egg?”

Finally, there is the monistic view – that there is no realistic possibility of analytically dividing superstructure and base in any manner that can help us to make sense of the evolution of political economy.

The problem with all of these views is that they are static analyses of what is essentially a dynamical system, so we will create a model which views it that way. In order to get a clearer view of how things unfold, it is useful to view three layers in the system rather than two: the forces of production (roughly technology), the institutions of production and the auxiliary social institutions and general culture. This three fold view is especially important in capitalism, where the forces of production are changing rapidly. By contrast former systems had very slow development of the forces of production and therefore it was not so critical to bring them into the picture.

At each time-slice we have a particular capacity to produce. This is conditioned by the time slice prior which had some forces of production and some social organisations of production which produced forces of production for the next stage. The social institutions of production are then faced with the environmental climate produced by the previous round. Similarly these organisations of production provide a new climate for the highest layer, the superstructure.

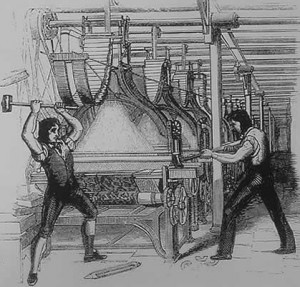

We can see how this might unfold with a specific case of the development of the power loom in the early 1800s. Once the power loom came into use, the price of fabric dropped tremendously. This drop in the price of fabric was facilitated by the lower amount of labour which needed to be employed in fabric production relative to hand-looms. This in turn destroyed the cottage industry niche which had supported independent household fabric production. The non-viability of cottage production gave rise to unemployment, which could then potentially be employed to other tasks and enabled even more growth of the power loom factories by providing a large pool of labour.

We can see how this might unfold with a specific case of the development of the power loom in the early 1800s. Once the power loom came into use, the price of fabric dropped tremendously. This drop in the price of fabric was facilitated by the lower amount of labour which needed to be employed in fabric production relative to hand-looms. This in turn destroyed the cottage industry niche which had supported independent household fabric production. The non-viability of cottage production gave rise to unemployment, which could then potentially be employed to other tasks and enabled even more growth of the power loom factories by providing a large pool of labour.

It also gave rise to huge social antagonism from those newly unemployed whose living standards severely diminished. We see here that the development of the forces of production creates a new environment for the base, the organisations of production. We have moved from cottage industry to factory industry because of a technical change provided by investment from a previous stage.

From the Top, Down

In which ways can the superstructure effect changes to the forces of production? It is virtually incapable of doing so, because at every stage it does not control the institutions of production. In capitalist society these institutions of production are things such as banks, stock markets, companies and corporations.

There is also a very important section of the productive sphere which involves the state. A huge proportion of the intellectual development necessary for developing innovations and technologies happens in universities or in state funded research as intellectual production (such as research and development) is less easy to obtain profits from directly and generally has to be longer term than capitalists would like.

The media exerts tremendous influence on the population and can even create cultural norms and yet it is not able to make lasers or 3D printers. Instead it can influence the evolution and development of institutions of production, as these institutions are composed of humans. This in turn can lead to the development of new forces of production.

The relations of production and the institutions which take part in these productive endeavours are a requirement for the reproduction of society. Further, the manner in which surplus from production is distributed is directly related to this configuration. As such there is a potentially massive domination over the superstructure from the productive base, since what channels of communication are open (whether that be cathedrals or television stations) are to a great extent moulded by these forces. The mode of production requires that certain social norms be followed and it promotes these social norms.

Even the reflection on this fact, the process of creating analytical theories about the method of production and then the dissemination of these theories is determine by the productive relations.

How can this be if we are capable of expressing opposition to the productive relations? It is because not all elements of the superstructure are produced, with intention by humans, with the aim of continuing the social relations of production as they are currently arranged. Instead the forces of production and the institutions which produce using them can give rise to spaces of antagonism.

There are in fact many who consciously direct the reproduction of the system: the IMF and the Central Banks, let alone the States’ security apparatus of the world aren’t there for the fun of it.. In general the ruling classes are much more acutely aware that such activity is necessary, and yet not all of what is enabled by the base is within the control of the ruling class.

If I write and analyse production I’m utilising access to a certain standard of living, access to my own time, access to education, access to information of the historical past and the capacity to utilise the networks of communication to disseminate such ideas which have arisen in the information age.

Similarly, under feudalism, the clergy, nobility and noble tutors (in the main) undertook the study of mathematics, chemistry, physics, engineering and biology. These tasks eventually yielded the forces of production which laid the basis for capitalism to take hold. The superstructure was not entirely devoted to the reproduction of feudal stasis, although there is no question that a huge proportion of the surplus was devoted to the tasks of reproduction of the relations of production.

This divergent space opened up by the relations of production which can give rise to new modes of production is essentially a contradiction in the system itself. Through its own reproduction it unconsciously provides the material basis for the evolution of the new.

Where from here?

This analytical framework has important consequences for socialists. Capitalism, especially in its more developed form, with its now enormous productive potential, has the capacity to give rise to a vast group of people capable of reflection on their own role in society. The contradiction is now much more important than the type experienced with a tiny elite in Feudal society. It instead opens up the possibility of a vast scale of egalitarian change.

However, the current relations of production have also used the vast productive potential to create the most sophisticated superstructure ever witnessed in history in the defence of the current relations of production. The elite which are the beneficiaries of those relations of production use the immense surplus to employ armies of sycophants which help to spread support for the the idea that it is impossible to move to other methods of organising production.

And yet the contradictions in the system are also quite visible. The enormous productive power is not giving rise to increased living standards for the majority of the population, but the converse. This has been noticed not only by some socialist fringe, but is visible in the centre of the most apologetic mouthpieces of the current system.

In order to utilise these contradictions it is necessary that we organise our own labour power in producing new productive relations with each other in order to further open up the contradictions. It is by wedging these open that we will allow the new world to be born.

- See for instance Anwar Shaikh’s work on empirical support for the thesis http://www.ehu.es/Jarriola/Docencia/EcoMarx/EcoMarx%20frances/labthvalue.pdf ▲

2 Responses to What is Historical Materialism?