This article is a response to an article posted on The North Star by Sophia Burns, a comrade and fellow member of the Communist Labor Party titled Don’t Run for Office. It can be found here: http://www.thenorthstar.info/?p=12742

This article is a response to an article posted on The North Star by Sophia Burns, a comrade and fellow member of the Communist Labor Party titled Don’t Run for Office. It can be found here: http://www.thenorthstar.info/?p=12742

The tradition of movements commonly grouped under the umbrella “the left” is diverse. It includes movements rooted in ecology, labor struggles, women’s’ struggles, fights against racism and many other currents. Likewise, the tactics employed by these groups have varied across time and space.

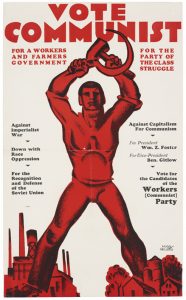

One of these tactics, standing candidates for government offices is perhaps the most divisive. In the early years of the socialist movement, the Marxists, and others, argued decisively in favor of using the popular assemblies conceded by the ruling coalition of classes to further the cause of the workers’ movement against the anarchists. The electoral socialists would create the movement known historically as “social democracy” which is distinct from the modern ideology using that name. Many communists, including those in the Marxist tradition, have argued since these days that the failure of social democracy in the early 20th century to achieve revolution is proof that the tactic of standing candidates for democratic assemblies in capitalist society is either outdated or was never correct to begin with.

The theory that electoralism is a dead end is primarily rooted in three arguments: 1) that the terrain of civil society is stacked against the workers’ movement and so its candidates are unlikely to be elected. 2) that participation in state organs produced by capitalist society necessarily leads to compromise of the values of the representatives or party in order to “manage capitalism” and 3) that even if you are elected and maintain your revolutionary principles through connection to the concrete movement, the ruling class will simply abandon the constitutional system to oust you (like in Allende’s Chile or when Yeltsin took power in the later years of the Soviet Union).

However, those not in favor of using electoral politics as a political strategy propose several alternatives: councilist faith in working class spontaneity, anarcho-syndicalism, anarcho-autonomism (which is a modern variant of classical platformism) and insurrectionism.

We will look at some of the anti-electoral arguments in turn.

1. “If Voting Changed Anything It Would Be Illegal”

A common mythology spread in Marxist and anarchist circles is that “bourgeois democracy” is a uniquely capitalist form of government. They theorize it was created in society by the capitalist class, rather than being forced by the workers, when they assumed power and began recreating society in their own image, and therefore it can only be used to capitalist ends.

However, this is manifestly not historically accurate. The progressive sections of the French Revolution, the Jacobins, were largely comprised of independent producers and the early working class rather than the manufacturing or merchanting capitalists. Even the reforms implemented by Napoleon were enacted because the freedoms of working people simply couldn’t be rolled back. As Vivek Chibber argues in Post Colonial Theory and the Specter of Capital, the capitalist class’ drive was towards centralization, while what democratic structures were won outside the realm of ideology were the product of the sublatern working class. Napoleon understood he needed to include many former supporters of the Jacobins and remake the hegemonic order to secure French imperial ambitions.

Also never to be forgotten were the Chartists, workers who bled in Newport to secure such radical demands as the end of property requirements for franchise and proportional parliamentary constituencies. Similarly, the democratic reforms won in Germany in the 1848 revolutions, were pressed for by the working class in their alliance with the “Democrats” who were more than happy to leave the revolution at the point of establishing the end of feudalism. The same is true of the establishment of the Weimar Republic, which in spite of falling short of socialism gave considerable concessions to workers politically. And, in the United States, fights for universal suffrage, direct election of senators, freedom of speech, and the emancipation of the slaves were actively spearheaded by the working class (and their farmer allies), especially among immigrant communities in the West.

When we look at purely bourgeois revolutions like the overthrow of the Articles of Confederation in favor of the Constitution in the US, we see a strong anti-democratic streak. Despite all the grandiose phrases about the equality of men, the constitution created the separation of powers and the institution of electoral college, the effects of which we see playing out in every election since the republic was founded.

Concessions like the Bill of Rights were not given out of idealism, but realpolitik out of fear of insurrections like Shay’s Rebellion, led by free farmers and laborers of whom Madison and Jefferson were the self-appointed political representatives.

Likewise, the white supremacist establishment in the United States south, after the “Redemption” overcame the Reconstructionist Republicans, did all in their power to limit the access of Black Americans to vote by introducing poll taxes, “literacy tests”, and blatant intimidation through violence and murder. It was defeated by the Voting Rights Act, won through mass mobilization of communities of color, the progressive faith establishment, radicals and the bulk of organized labor.

Beyond the USA, the English Revolution, under Cromwell and his monarchist successors, as well as the liberal reforms of Alexander II of Russia, demonstrate the capitalist class’ preference for exclusion of the working class from the political life if at all possible. The democratic republic, as opposed to a pyramidal council republic, or decentralized confederation of communes, is one possible form that the socialist state can take and is the one most likely to take hold in the United States for cultural and economic reasons. Such a republic would need to be radically more democratic than any which has existed before and there is no reason that some of this democratization can’t be done by socialists along our road to power. That isn’t to say that we can simply “vote in” socialism in any conceivable revolution, at least without enough strength behind us that the capitalist class knows it is beaten, but many social organs that are currently a part of the state can serve as scaffolding on which to build a new state that serves the whole people.

Emma Goldman once said that if voting changed anything it would be illegal. If the bloody history of workers, women and oppressed people fighting for the right to access the vote demonstrates anything, it’s that voting is indeed an effective vehicle for change. It’s through the power of working class institutions like unions and independent media that the right to the vote and participation in formal politics are safeguarded for working people. This is why the assault on democracy has taken place in the US after the back of organized labor was finally broken in conditions of rising worker militancy where in Europe, the assault of capital is still focused on labor and economic concessions.

2. “Running in Rigged Elections is a Waste of Time”

This then inexorably leads us to today. In the United States, there are numerous examples of anti-democratic efforts carried out by the capitalist state: programmers have gone on the record admitting to rigging electronic votes, restricting access to polls, purging voters from rolls, and overturning the campaign finance reform.

In Europe we also see similar [anti-democratic] trends, such as the raising of vote requirements for parties to gain seats in the legislature, criminalization of democratic protest, as well as the formal criminalization of left wing political parties deemed “extremist”. To the abstentionist, these forces aligned against the working class movement’s electoral prospects seem clear proof of their views but in reality the reverse is true.

Democratic reforms are make sense to the vast majority of people existing in capitalism and are themselves a vital demand for any revolutionary minimum program. They also serve as a strong basis for propaganda. An example of such reform is implementing proportional representation on the state and local level, as well as in a patchwork manner on the federal or preferential voting. The fight to win such democratic reforms bolstered the Industrial Workers of the World in its early 20th century heyday, via the Free Speech Fights, and helped to build communist led institutions like the ACLU, that only under the repression of McCarthyism fell from the grasp of the working class. Running candidates on the basis of concrete democratizing demands, even if they fail to get elected, is a means of winning people over to socialism, which is in its essence the democratization of the whole of society.

It is certainly true that the electoral terrain is stacked against political movements that do not already have institutional backing. However, electoral socialism does not necessarily take place in the context of a revolutionary sect, without a real connection to a mass base of workers, fielding candidates to attract people to its program.The characterization of all electoral work by communists and socialists as such by abstentionists is disingenuous. In The Road to Power, Karl Kautsky outlines the aim of the working class movement under capitalism as to build independent institutions, or take and transform existing institutions, from capital, unions, cultural organizations, mutual aid societies, cooperatives and so on, which can then be used as a mass base upon which to contest parliamentary struggles and enact reforms which will enable this mass base to grow. A workers’ party needs to contest all areas of struggle, political, economic and social, both to demonstrate that it is a party of mass action and to use victories in each to reinforce the others.

Claims that under the present political regime working class candidates are at a structural disadvantage aren’t wrong, they simply ignore our ability to level the playing field. Similarly, the idea that because electoral work as a practice creates unhealthy dynamics for building concrete class power in a situation where there is a vacuum of working class institutions means that electoralism in and of itself is invalid does not logically follow. Contesting elections should be done when there is a clear political advantage to capturing specific state organs, like city councils or state legislatures, in order to make the ground more fertile for proletarian organs. Socialists who root their politics in a firm analysis of the history of the working class movement as a whole applaud abstentionists for denouncing attempts to run presidential candidates by left wing parties under present conditions, but remind them in a comradely way that present conditions are not immutable.

3. “Participation in ‘Bourgeois Government’ is Inherently Corrupting”

In their polemics against electoral efforts by socialists, abstentionists often argue that participation in bodies whose primary function is to regulate capitalist society end up necessarily moving rightward in order to effectively participate in government. They cite SYRIZA and Mitterand’s Socialist Party among others to bolster their claim that since some parties that claimed to be leftist capitulated to capitalism it follows all will. However, there is a qualitative difference between how say SYRIZA, or Podemos approach electoral participation and how the pre 1914 Social Democratic Party in Germany (and its Scandinavian contemporaries with the Norwegian Labour Party even joining the Comintern at one point) or Communist Party of Italy under Gramsci and later Togliatti did so.

In 1976, after 25 years of labor oriented social democratic reforms which gave unions an increasingly strong role in the economy, Sweden’s trade union confederation, LO, adopted a proposal for the socialization of firms by taxing profits and using them to buy stock at a rate which would make most firms 51% employee owned within 25 to 30 years, and eventually wholly owned, as a means to deal with the distorting effects of capital concentration on the social market economy. The Social Democrats, although less enthusiastic on the whole, having a vocal liberal current, also adopted the proposal. Following their electoral defeat, due to a variety of factors, the Social Democrats moved closer to the Third Way consensus and watered down the proposal when it was finally enacted beyond recognition. However, had the election been won, the original unmodified, or only slightly adjusted, socialization proposal would have been introduced as a part of the democratic mandate. This example shows that it is possible, though difficult, to make genuine socialist economic reforms provided the working class has strong enough institutions of its own to pressure the political establishment as hard as the capitalist class does.

The notion that it is structurally impossible to replace capitalism with socialism through parliamentary means reifies the state and fails to recognize what it is: a battleground, among others, for various class forces as well as the technical apparatus for the administration of a specific form of society. Of course we’re not going to win socialism through the democratic assembly as a movement when the global workers’ movement is at such a low point but the conditions of this moment are not transhistorical. And of course we can’t just take the ready made technical apparatus of social management of the existing state and apply it to socialism; we have to metabolize it.

Even if these parties themselves would be co-opted by right wing social forces due to specific international historical conditions, the first world war on the one hand and the degeneration of Soviet socialism on the other, their policies were militantly democratic, socialist and progressive. It was the groundwork they laid, changing people’s’ lived practice and expanding class consciousness that gave birth to the movements that would carry on their legacy and propel the workers’ movement forward, the Spartacus League and KPD and the Autonomists in Italy. Some abstentionists argue that the periodization of elections to democratic assemblies under capitalism make them inherently corrupting because they normalize the practices associated with getting elected, gathering votes and so on which requires a revolutionary party to adjust its internal structure in a way that somehow undermines their revolutionary work in other areas.

It’s true that a small party which, having few resources and members, orientates itself almost wholly to electoral organizing would do so to the exclusion of other forms of struggle; but this doesn’t hold for a party which has established a mass base in a given region and therefore has more resources to commit to different areas of struggle. This could be said to be a dialectical transformation of quantity into quality; when we are a small party and disorganized, the communists should not field candidates but focus on building a social base, and when we are a developed party with functional ties to independent social organs, we must engage with electoral work or be crushed.

Similarly, criticisms of Chavismo on the basis of its failure to transform Venezuelan society into a socialist one through electoral means fails to engage with that revolution in good faith. Chavistas never promised that the state would seize production on the soviet model like the People’s’ Democracies did after the second world war, but instead promised they would use the state to facilitate worker self-emancipation, the creation of collectives, improving literacy, supporting factory occupations and so on. It’s precisely the self-emancipation of the class that abstentionists and left wing communists want so deeply that Chavismo is ideologically structured on. Regardless of the failures of policy under the Chavez and Maduro governments, such as the dual currency system and overreliance on oil exports, as we speak workers are running factories themselves, people are organizing into communes and the fight against the economic war of capital is being taken up by the workers themselves. The abstentionists simultaneously demand that we wait for a far off revolution after years of employing their prefered strategy be it syndicalist, platformist, or autonomist, while also demanding that the electoral strategies prove their success immediately after representatives take office and fail to recognize that electoralism can be a small part of a much larger strategy.

4. “None of it Matters Because the Capitalists Will Just Suppress Us Anyway”

The third line of attack abstentionists level against advocates of electoral participation is that past experiences have demonstrated that revolutionary groups who do capture the legislative or executive bodies of a state within a democratic constitutional framework are inevitably overthrown by the capitalists who are more than happy to violate the very democratic principles they supposedly operate on. There is some merit to this criticism, insofar as it is an issue that many communists who seek to take the democratic road fail to consider; however, it fails to account for the fact that this very same reality applies to their own proposed policies. One only has to look at the criminal syndicalism laws of the United States, the use of fascist thugs to attack leftists and their organizations, or the suppression of cooperatives in Spain during its period of liberalization to see that the capitalist state has no compunction with using legal and extralegal means to suppress dual power organizations. There’s no objective or material reason that once dual power institutions, be they red unions, cooperatives or serve the people projects became a threat to the establishment that they wouldn’t be crushed or dispersed with arms just like a red parliamentary majority, and with an honest evaluation of history we can see they have been.

The notion that we can build self-sustaining and growing social bodies which produce socialist ways of living to supplant capitalist systems of social reproduction, without participation in electoral bodies, ignores the fact that not only can the state intervene but so can private capitalism. Without a stake in local governance, the most we can do when capitalist gun-thugs come to evict our squats or banks call in the debts of our cooperatives is to beg for help from saviors from on high. When the Communist Party and Socialist Workers’ Party members were arrested they were only saved by pronouncement by the Supreme Court, and even then, their mass organizations like the International Workers’ Order and many cooperatives were smashed up with no possible recourse.

Notions of self-defense of the class are well and good, and even necessary, but can a plucky band of cooperative grocers, picketers, free store operators and teachers, in conditions long before we have the majority of workers on our side, really be expected to put up armed resistance against the militarized police? The conditions where autonomist theories of self-organizing workers who could replace the capitalist economy without needing to rely on electoral institutions, emerged were precisely conditions where mass electoral participation and an already existing formal ecology of socialist institutions had already won significant legal and social space for these forms to exist in. The material conditions of that movement do not exist in the United States today. This isn’t to say those theories are not worth engaging with, but that their strategies have to be critically examined instead of being pasted onto a very different period of the class struggle.

Further, when advocates of electoral participation say that running candidates and holding office is a legitimate tactic for the struggle they do not necessarily advocate a pacifistic approach to revolutionary transformation where the capitalists could suspend democracy without consequences. Instead, the vast majority argue for building the capacity of the class for self-defense when it comes to that. It should never be forgotten, as it often is by leftists that the Paris Commune began as a cross-class city council and became revolutionary on the basis of a proletarian majority, elected by democratic vote.

As Engels said in his preface to The Class Struggles in France:

And if universal suffrage had offered no other advantage than that it allowed us to count our numbers every three years; that by the regularly established, unexpectedly rapid rise in the number of votes it increased in equal measure the workers’ certainty of victory and the dismay of their opponents, and so became our best means of propaganda; that it accurately informed us concerning our own strength and that of all hostile parties, and thereby provided us with a measure of proportion for our actions second to none, safeguarding us from untimely timidity as much as from untimely foolhardiness—if this had been the only advantage we gained from the suffrage, then it would still have been more than enough. But it has done much more than this. In election agitation it provided us with a means, second to none, of getting in touch with the mass of the people, where they still stand aloof from us; of forcing all parties to defend their views and actions against our attacks before all the people; and, further, it opened to our representatives in the Reichstag a platform from which they could speak to their opponents in Parliament and to the masses without, with quite other authority and freedom than in the press or at meetings. Of what avail to the government and the bourgeoisie was their Anti-Socialist Law when election agitation and socialist speeches in the Reichstag continually broke through it?

With this successful utilization of universal suffrage, an entirely new mode of proletarian struggle came into force, and this quickly developed further. It was found that the state institutions, in which the rule of the bourgeoisie is organized, offer still further opportunities for the working class to fight these very state institutions. They took part in elections to individual diets, to municipal councils and to industrial courts; they contested every post against the bourgeoisie in the occupation of which a sufficient part of the proletariat had its say. And so it happened that the bourgeoisie and the government came to be much more afraid of the legal than of the illegal action of the workers’ party, of the results of elections than of those of rebellion.

And after discussing the forces that insurrectionary attempts at seizing power will face and how the tactics contemporary revolutionaries supported were outdated, Engels continues that the elected forces of the workers’ movement are nothing less than the shock troops of revolution. Engels does not call for timidity like the reformists, instead he says

But do not forget that the German Empire… and generally, all modern states, is a product of contract; of the contract, firstly, of the princes with one another and, secondly, of the princes with the people. If one side breaks the contract, the whole contract falls to the ground; the other side is then also no longer bound [as Bismarck showed us so beautifully in 1866. If, therefore, you break the constitution of the Reich, then the Social-Democracy is free, can do and refrain from doing what it will as against you. But what it will do then it will hardly give away to you today!].

While quoting dead revolutionaries as an authority to justify a position rather than directly gathered material facts is not scientific I cite Engels here because he puts the strategy, that he proposed as a result of scientific analysis of the class struggle he himself took part, in in much more eloquent terms than I ever could. As the late wobbly troubadour Utah Phillips said, “Yes, the long memory is the most radical idea in this country. It is the loss of that long memory which deprives our people of that connective flow of thoughts and events that clarifies our vision, not of where we’re going, but where we want to go.” While we should engage with dead revolutionaries critically, their writings are a part of our collective memory and we shouldn’t be so temeritous as to think that with their lives spent critically examining scientific principles of revolution they have nothing to tell us today.

By occupying elected bodies, during periods of class peace, revolutionaries can “gum up the works,” so to speak, and reduce the capitalist state’s ability to suppress the independent organizing workers towards dual power. During conditions of open class war, when the norms of democratic society are suspended, we are likewise free to abandon democratic convention. Refusal to occupy these seats only allows a legitimate constitutional means for our suppression instead of forcing the capitalist class to show their true colors. Citing the overthrow of Salvador Allende as proof that there is no electoral road to socialism only shows that faith in the electoral system alone, without the credible threat of force that can be used in self-defense, is insufficient for socialism.

5. The “Successes” of Abstentionism

The manifest failure of many past socialist movements that participated in elected governments to secure power for the working class is ironically a much better record than the complete failure of revolutionary groups that advocated strict abstentionism to do so. Nearly every communist movement which successfully secured power for any amount of time from the socialists of the Paris Commune, to the Bolshevik Party, and the Communists in Cuba had participated in electoral work in order to build their movement. Whatever their failures after securing power, these parties and groups did in fact establish proletarian dictatorships, that is to say economically democratic regimes, for at least part of their existence. Conversely, the only revolutionary situation where self-professed anarchists successfully established a socialist system, they did so with elected representatives in the Spanish popular front. Where are the successful platformist, anarcho-syndicalist, or council communist revolutions? What lasting changes have they won for the working class that didn’t involve the aid of electoral socialists? Looking at the history scientifically, all available experimental data shows that the hypothesis of abstentionism as a workable strategy for interfacing with political organs to be a failure in building class power.

A recent case-study is the class struggle in Ireland. By looking at the recent history we can see how in an advanced capitalist country two strategies , abstentionism and revolutionary electoral work play out. On the one hand, the Workers’ Solidarity Movement, a platformist organization formed in 1984, adopted a program of dual power building without contesting elections. This organization did have many successes, actively participating in the labor movement, abortion rights access and antiracist work. Their mass work led them to a growth from 12 members in 2001 to 60 in 2008. However, by today their membership has collapsed down to numbers close to 2001 and while their zeal for mass work has not faded, the resources they can commit to any given struggle has suffered accordingly. Contrast this with the Socialist Party, an ostensibly Trotskyist outfit, which has engaged in the same struggles while also committing resources to electoral campaigns under the banner of the Anti-Austerity Alliance and has secured three representatives in the national parliament for itself and six for the broader coalition. The Socialist Party emerged out of a split from the Labour Party in 1996 out of its small left wing and today the Anti-Austerity Alliance has only one less TD (member of parliament) than the Labour Party. This electoral participation has, rather than turning the SP from its social base, enabled it to commit more to dual power organizations like ROSA, which is dedicated to women’s liberation and providing abortion access, even illegally, to Irish women. The growth of the Socialist Party is directly tied to the issue of water charges which they have campaigned against and have helped get a large majority of citizens to refuse to pay. Electing members to government have only helped them gain a platform for further struggle without any need to compromise their positions and moving to the right. By having TD’s the Socialist Party is able to draw the attention of the capitalist press to issues they would otherwise ignore and they are able to make meaningful changes in local councils where they have seats. Like many Trotskyist parties, the Socialist Party overemphasizes the role of the electoral party against the ecology of workers’ institutions that it relies to and so the content of their electoral proposals suffer accordingly, for instance, rather than advocating for mutualization of firms they’re pushing for a better welfare state. Their line is based on the outdated “transitional program” model. But the flaws of their particular strategy only serve to demonstrate that electoralism works, even when done by unscientific revolutionaries.

The vision of building socialist dual power without any sort of electoral participation is at best teleological, that is to say puts blind faith in inevitable progress, and at worst dangerously naive. The abstentionist nostrum to co-optation, “direct democracy” is no solution to the real problems of building the socialist movement. History is contingent, not formulaic; It does not follow neat patterns where certain tactics lead to inevitable results. Practice must be dynamic rather than fixed according to idealistic conceptions of what socialist modes of life are. We can’t simply prefigure the world we want to live in in our organizational forms, while existing in a society that is by its very nature hostile to those forms. Direct democracy is proposed as a panacea, or cure-all, for the potential difficulties faced by revolutionary social organs but it doesn’t really solve anything as shown by historical example and merely repeats the errors of the council communists.

In 1919, the German revolution produced directly democratic workers’ councils all across the country that were heralded, by those to the left of the Communist Party, as in and of themselves constitutive of revolutionary transformation. After-all, didn’t having bodies where workers would directly make decisions make them inherently revolutionary? Unfortunately, these same organs elected by large margins the Social Democrats, who had turned against the revolution early on, and Independent Social Democrats, who were willing to sacrifice the revolution to maintain an alliance with the former since that’s where the majority of workers were. The SPD would go on to dissolve the workers’ councils in favor of a capitalist republic that they created in alliance with the liberals. Time and again we see the same types of failure that abstentionists point to with electoral participation appear in directly democratic institutions. This is not to say that direct democracy is bad or not necessary for a socialist society, but it is clearly insufficient and does not actually solve the issues that plague many historical elected parties.

6. Reform and Revolution?

The role of electoral work is a divisive one on the left and an issue over which much ink will be electronically spilled for decades to come. However, it is clear that from the perspective of scientific socialism electoral work is a necessary, but not sufficient, component of the work that a workers’ party will need to undertake. When, in conditions of a fractured and disorganized left with no revolutionary base, the situation all professed workers’ parties in the United States find themselves in, electoral work is a distraction from the more important social work that must be done. But once such a base is secured, operating in and through legislative bodies is a necessary precondition for facilitating that very same base’s continued growth by hindering reactionary legal suppression and enacting reforms that improve the structural position of workers and oppressed people beyond modest increases in living standards which social democrats fight for. Rather than abandon an entire field of struggle in the war of position against capital, the revolutionary party should adopt a position of revolutionary defensism. Revolutionary defensism is the idea of using legal means as they are available, and struggle to increase their availability, while not refusing to use methods outside legality, and preparing for the inevitable violent reaction of the capitalist class.