Today, more than it has in the past, the topic of violence is one that is being debated hotly, especially in the aftermath of the Occupy Wall Street movement, the workings of SYRIZA in Greece, and the wave of unrest in the Arab world.

To the Utopian socialists, violence was abhorrent: many of them had been appalled by the supposed excesses of the French Revolution. In line with their view of the progress to a socialist society as one that was not based on class but an appeal to reason and enlightenment, the cooperative society based on common ownership was to take place as a result of social experimentation (cf. New Lanark and the various utopian communities established in America1) and long-term peaceful transition by building model societies and education which would attract all lovers of reason and humanity.

Nevertheless, this is decidedly not the attitude that the socialist movement would take in later years: although it was obviously never universally accepted, especially among the somewhat-relevant Utopian sects still in existence, violence was seem as both legitimate and necessary, especially on the continent (socialism was not a major political force in England at this time, and in America it was virtually nonexistent). This was during a time when states in Europe and North America were much more authoritarian and heavy-handed than they are now, and the methods of capitalist repression far more brutal, and thus the need for violence was not really disputed at all: socialists took part in all sorts of violent actions, from conspiratorial insurrections to popular revolution to more mundane but still violent confrontations in the class struggle, such as self-defense of workers against repression by the capitalists. In addition, where socialist organizations were illegal (as they often were), the idea of a pacifistic policy seemed rather out of place, to say the least.

Nevertheless, during the late 19th century, the issue became a bit more contentious. Socialist parties throughout the capitalist world became more powerful in numerous ways: culturally, politically, and especially numerically; also, states had become far less autocratic and far more democratic, with the introduction of (aside from France and Britain, admittedly limited) legislatures in which socialists could field candidates either independently or as a party (these places also made great propaganda platforms in an era where freedom of speech outside parliament was rather limited in certain circumstances). In addition, military tactics and technology had come a long way since 1848, which still weighed heavily on the traditions and mindsets of many socialists. This was when military technology started to assume more modern forms: muskets were replaced by rifles, and repeating ones at that; artillery had become far more advanced, being able to fire more accurately, harder, and faster; the new planned layouts of many cities were not very conducive to street-fighting. Quite famously, after 1848, Paris was redesigned entirely and one of the express purposes for building the wide boulevards the city is famous for was to prevent effective urban insurrection to begin with: as the experience of the Paris Commune in 1871 shows, it worked; and, finally, the nations of Europe had grown new, huge, professional standing armies, which were far more trained and mobile than the forces of before, which, in comparison to these new military forces unleashed upon the world, were laughable. These factors combined to make the formerly unshakable belief in the necessity or at least the preference of violence somewhat shaky.

The position that eventually settled down as the mainstream one was somewhat of a balanced view of violence given the situation. On the one hand, there was the possibility of electoral victory, especially in countries such as America, Britain, and France; on the other hand, violence was not ruled out entirely. Marx said in 1871 at a speech to the IWMA:

“The congress at The Hague has brought to maturity three important points:

It has proclaimed the necessity for the working class to fight the old, disintegrating society on political as well as social grounds; and we congratulate ourselves that this resolution of the London Conference will henceforth be in our Statutes.

[…]

But we have not asserted that the ways to achieve that goal are everywhere the same.

You know that the institutions, mores, and traditions of various countries must be taken into consideration, and we do not deny that there are countries — such as America, England, and if I were more familiar with your institutions, I would perhaps also add Holland — where the workers can attain their goal by peaceful means. This being the case, we must also recognize the fact that in most countries on the Continent the lever of our revolution must be force; it is force to which we must some day appeal in order to erect the rule of labor.”

Likewise, Engels, in his now famous introduction to Marx’s The Class Struggles in France, 1848 to 1850 gives a similarly balanced assessment, as well as addressing some of the issues that I myself briefly touched upon above. According to Engels, while electoral victory is possible, it is still not necessarily guaranteed or even likely. However, socialists should use parliament to its fullest extent, and if they are prevented from taking hold of the state by means of force then the socialists themselves are no longer bound to legality and violence may be used free of any charges of instigation and in a generally superior position all-around.

For a while, this constituted the basis of the strategic orientation of the socialist parties of the Second International, combined with a belief, at least in the SPD, of the collapse of capitalism (Zusammenbruch, which quite literally means to break down or collapse) at some time in the future, which would then provide the basis for the socialist takeover of the government. There were, of course, dissenters, from both the left (like Sorel and the syndicalists) and the right (notably Bernstein), but this was the general view among socialists at the time.

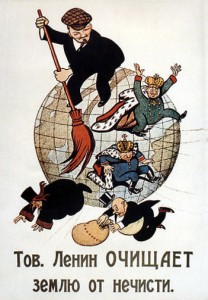

However, Russia conspired to challenge this view. Even before the October Revolution, at least two Russian Marxists had come to the conclusion that one could not simply “take over” the state: Nikolai Bukharin, in his analysis of imperialism, and Vladimir Lenin, who claimed to have reconstructed the Marxist theory of the state from theoretical distortions in the Second International. Not only this, but in 1917 the proletarian revolution in Russia occurred; the urban proletariat and the Bolsheviks overthrew the provisional government and set up a soviet government, later calling elections to the Constituent Assembly but dismissing the body shortly after due to disputes about the party lists2. While the initial takeover was forcible but not bloody (not a single shot was fired), the Soviet state was later involved, during the Russian Civil War, in conflict with counter-revolutionary forces and various other factions, which constituted the real bulk of the revolutionary fighting and the consolidation of the revolution’s grasp on the country.

According to Lenin, the experience of the Russian Revolution had shown in practice one of the lessons on the Marxist theory of the state and of revolution that had allegedly been buried or misunderstood: the theory that, contrary to parliamentarian and electoral approaches, the bourgeois state had to be smashed. The state as a bureaucratic-military machine cannot be seized and wielded by the workers as is or with merely a few touch-ups. Although Lenin also acknowledges, like Marx, that in England and America there was a period of time where the character of the state there allowed for a peaceful seizure of power, the development of imperialism has rendered this impossible, and now even these states are to be smashed. He writes in The State and Revolution:

“Today, in 1917, at the time of the first great imperialist war, this restriction made by Marx [of the necessity of force to the continent] is no longer valid. Both Britain and America, the biggest and the last representatives — in the whole world — of Anglo-Saxon ‘liberty,’ in the sense that they had no militarist cliques and bureaucracy, have completely sunk into the all-European filthy, bloody morass of bureaucratic-military institutions which subordinate everything to themselves, and suppress everything. Today, in Britain and America, too, ‘the precondition for every real people’s revolution’ is the smashing, the destruction of the ‘ready-made state machinery’ (made and brought up to the ‘European,’ general imperialist, perfection in those countries in the years 1914-17).”

Therefore, in Lenin’s view, the possibility of peaceful transformation and the coming to power through parliament was over, however limited it might have been in the first place: the socialist revolution can now only come about through violent insurrection of the bourgeois state and its replacement by a proletarian one. This remained, in one form or another, the general view of Marxist socialists until the modern time, although in the mid- to late-20th century the “eurocommunist” view revived the notion of working through parliament.

So this brings us to the present day. What is to be the communist orientation for the modern day and our modern conditions? There are certain ways in which we need to investigate this.

First of all, we must refuse to accept the view that we must a priori reject the use of violence. If violence is necessary, communists will use it. It is said that Leon Trotsky had once said that not believing in force is the equivalent of not believing in gravity: and in the realm of proletarian politics, it is. The need for violence is determined by the social context: it is beyond us to deny that there are situations where it is legitimate and useful to use violence, and in fact where it is the only way to effect forward progress in the proletarian movement. In such a situation, opposition to violence would be equivalent to siding with the counter-revolutionary forces: when the proletariat is confronted with an obstacle, or being shot at, etc., to say that the correct response is to not confront it or to take the bullets with dignity is treason to the proletarian cause. Likewise, all moralistic sentiments about eschewing the use of violence forget that the existing system, which subjects not only current but future generations to death by hunger, war, genocide, and imperialism, and is thus in the long run a million times worse than the deaths caused by a revolutionary civil war or a Red Terror.

Second of all, we must do away with the opposite error, the worship of force and struggle as things good in and of themselves. As Engels said of the possibility of peaceful transformation, “It would be desirable if this could happen, and the communists would certainly be the last to oppose it.” Violence is ultimately a means to an end, and just another possible tactic: its desirability cannot be established beforehand, just as its undesirability cannot.

Based on these two points, I will give my opinion about what the general orientation towards violence in our political practice should be for socialists today.

First of all, violence is necessary in self-defense against the capitalist class, and in every area of the globe where the capitalist class is forcibly attacking the workers, as in today happening in the peripheries of the capitalist world with extreme brutality, the workers have every right to shoot back. Likewise, lesser acts of violence, mainly in the core capitalist countries, can and indeed ought to be responded to appropriately if the movement is not to be crushed before it can really mature.

Second of all, violence is absolutely necessary as a tactic where revolutionary work is illegal and the state is blatantly undemocratic and therefore legal routes are impossible to pursue.

Third of all, Lenin was correct when deducing the impossibility of parliamentarian approaches to reach a satisfactory goal in 1917, and unfortunately his analysis holds up even better today. Although the electoral successes of SYRIZA and the “left” in Europe generally had seem like shining lights pointing the way, in reality their light blinds us: they show us the possibility of going into electoral politics and doing moderately well in the polls (fantastically well I should say, given our general popularity elsewhere), this is true, but it is also true that these same politics are fundamentally limited. First of all, there remains the same threat that Engels identified in 1895: the possibility of a counter-revolutionary coup. We have seen this in action several times, not only with socialist parties but even with non-socialist parties unfavorable to large sections of the bourgeoisie or the state bureaucracy and military. The most famous example, of course, is the overthrow of the Allende government by Augusto Pinochet in 1973. We could cite another Latin American example with the 1954 coup d’état and overthrow of the Jacobo Árbenz government in Guatemala where a leftist government was deemed a threat to the US state geopolitically and, to the largest landowner in Guatemala, the United Fruit Company, financially. A European example is forthcoming as well: the 1936 overthrow of the Popular Front government in Spain by Francoist forces. The list goes on. While this certainly opens up the opportunity for legitimate armed struggle, which happened in Spain with the outbreak of the civil war, it totally destroys the notion that a “peaceful” transition is possible and that one cannot “utilize” the bourgeois state for socialist purposes, and also illustrates that the proletariat must come to terms with its class enemy, one way or another, in revolutionary civil war, unless we are so exceptionally lucky as to have a bourgeoisie which keels over and doesn’t fight back3.

In addition, even allowing the possibility of a really socialist party ascending to power in parliament, it would find the other limit of parliamentary activity: the fact that, as Lenin says, parliament is not the “center” of power and never can be for that matter. Since the advent of imperialism and the massive expansion of the state and military bureaucracy, the legislature has had to contend with this bloated machine. Parliament has to contend with the mechanisms of the state’s own unelected bureaucrats, its civil servants, armed forces, etc., and therefore these needs balance out the so-called absolute power of the parliament. In addition, if it is not a major hegemonic power like the United States or China, its own capabilities are limited by geopolitical needs: a small country like Belgium with a socialist government would, due to its interdependence on the world market and the enormous pressure of the US state, be compelled to move in certain ways for its own survival and if it did not want to commit political and social suicide. So even getting into parliament is not a guarantee for a socialist transformation, having to balance oneself against both an antagonistic bureaucracy and capitalist pressure from the outside.

The violent overthrow of the government does not protect oneself, of course, protect oneself from outside governments; in fact, it makes them more liable to attack. However, this sort of conflict deals with the issue of outside interference in a sort of way, i.e. actually opposing them as opposed to grudgingly going along with their general will, that a dedicated peaceful approach cannot (otherwise it runs the risk of turning into a violent approach!).

But before those problems can even be considered, we must deal with the issue of even getting elected to the first place arises. This is not an easy task. In many cases the bourgeois state is not as easily won as getting a simple majority; regarding the intricacies of the American constitution, for example, and how nigh-impossible it is for any one party to control the government, much less a socialist party which gets dismal results to begin with because of a combination of a first-past-the-post system and gerrymandering, this article is a good one. While this problem is not necessarily as pronounced in other countries, it always exists in some form or another. Bourgeois democracy “is always hemmed in by the narrow limits set by capitalist exploitation” indeed!

Given the above reasons, the only option available to us as socialists is the calling for the replacement of the old state machine by a new, proletarian one — and this includes, unfortunately for those of us who are pacifistically inclined, the use of violence.

- Some of these still exist today, although it suffices to say that we are not yet living in a socialist society. ▲

- The dispute was specifically over the split in the Socialist-Revolutionary Party which had occurred prior to the elections. When the election lists were drawn up, the two main factions, the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries and the Right Socialist-Revolutionaries, were still one party; however, when, after getting a majority in the Second All-Russian Congress of the Soviets, the Bolsheviks overthrew the existing government, the Socialist-Revolutionary party was split over the issue, with the Left SRs being supportive of the Bolsheviks (until their resignation after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, Left SRs even held positions in the Sovnarkom) and the Right SRs opposing the Bolshevik revolution and supporting the provisional government and the eventual calling of the Constituent Assembly (not very surprising — Kerensky, leader of the provisional government, was an SR). The party lists for the elections when they were eventually called after the revolution, however, failed to reflect this: the Left and Right SRs were listed as a single party, and hence the Bolsheviks claimed that the Left SRs lost seats to Right SRs because supporters of the Left SRs had to vote for the SR party. ▲

- Which is a position taken quite seriously by the Socialist Party of Great Britain ▲

7 Responses to Violence and socialism