After having received 12 years of schooling in Ireland, I think it’s not too outlandish to say that history is a means to the formation of national identity, one which inculcates in the population a more or less patriotic conception of reality that binds them to present social system.

It is very much comparable to what is attempted by the Catholics in the sphere of religion, via the daily dose of indoctrination that is pumped into the heads of 90% of pupils in the country, and which, until recently at least, ensured that the vast majority identified as Catholic regardless of their views on transubstantiation or the Arian heresy.

Nor is this necessarily a bad thing, repugnant though it sounds to the modern libertarian temperament. Societies, in order to function as societies, as opposed to a merely Thatcherite aggregate of individuals, depend on value systems and the ideologies that justify them.

The Thatcherite model is probably not sustainable in the longer run as it leads to a war of all against all, which weakens its internal cohesion and consequently leaves it more vulnerable to external opponents.

Capitalism, especially its ultra-liberal guise, is the equivalent to pouring a never-ending stream of acid onto all ideologies, leading to their dissolution as a means of giving coherence to social life. This was, of course, identified by Marx and Engels as long ago as The Communist Manifesto, but it applies not just to the inherited ideologies of previous eras but to all ideologies including the secular ones that arose to fill the gap left by the declining religions. In this sense, the fracturing identified by post-modernist theorists is the conceptual framework most in keeping with capitalism’s inner nature.

It is worth thinking about why capitalism should have have such a corrosive effect on all ideologies.

Since capitalism depends on always selling new things — for who would cough up for what they already own — it necessarily fosters, through advertising, peer pressure, and built in obsolescence, a mentality of chasing after the eternally new, whether they be consumer goods or ideas. For most of history fashion was the preserve of the ultra-wealthy but with the rise to dominance of the capitalist mode of production the masses were forced into near total dependence on access to the market as the means of securing the goods necessary for their own survival. Arising from this universalising of market relations, fashion assumes a mass, unprecedented scale.

As attaining all goods via the market becomes normalized, society’s values gradually shift into line with this particularly dynamic mode of production. Whereas the preservation of tradition is the hallmark of pre-capitalist cultures, as is evident by the continuity emphasized by nationalist and religious movements, fashion, that signal of the eternally new, is the distinctive attribute of the era of high capitalism.

Movements of radical opposition are not immune to the penetration of this inherently capitalist mentality, as the ethical feeling that motivates so much social justice activism internalizes the need for the new new, both in terms of issues to focus on (the environment, the third world, sexual liberation) or new forms (consensus decision-making, participatory meetings, loose networks) while rejecting the old: the trade unions and the party form.

The mania extends to the desire to find new subjects of revolutionary opposition, e.g. the rejection of labour in favour of a community of the oppressed with its massive emphasis on personal identity — invariably unique! — as the key to revolution.

That tendency assumed absurd heights in parts of the recent Occupy movement with its rejection of co-operation with unions and telling people to leave their party politics outside. The past, according to this worldview, is intrinsically worthless. If the discovery and application of new issues and new tactics is the order of the day, then what need of knowledge of the past at all? The consequence is that activists live in a blissful state of ‘the eternal now’, unperturbed by the bland reality that much of what they think of as new — consensus based assemblies to take but one example — are themselves simply echoes of the New Left of the 1960s who themselves were scathing of the then ‘old’ left.

The obsession with newness is a double-edged sword, however. Participatory assemblies soon get old; phenomena like Occupy pass ever more swiftly from youthful exuberance to senile decay. Lacking the staying power that movements intent on building institutions generally have, they are subject to the whims of fashion that brought them into existence in the first place.

Since the construction of long-lasting institutions requires theoretical support, opposition projects which embrace the necessity to develop a stable ideological base run the risk of being perennially out of fashion.The sheer difficulty of overcoming that quintessential handicap of our time is not to be underestimated. But we are not totally defenseless; one of the strongest cards we have in building socialism is the link to the historical struggles of the past.

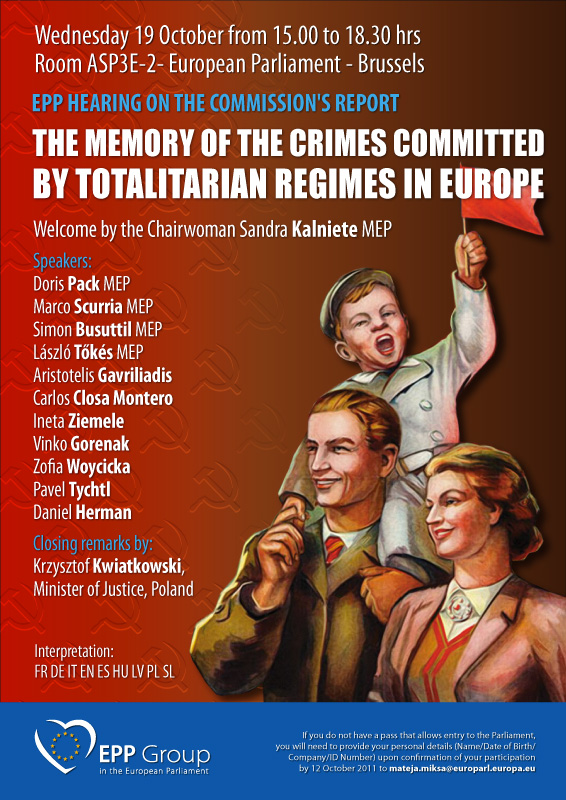

And so it was that at the recent Summer University of the European Left, a session on the struggle about history caught my attention. The immediate context, as outlined by host Sigfrido Ramirez, was the European Parliament’s funding of a museum called the ‘House of European History’ which traces Europe’s evolution from a continent riven by wars, revolutions and ideological divergence to one that has, seemingly, resolved the ideological question by settling on a liberal form of capitalism and dealt with the issue of war by pursuing loose integration via a technocratic run European Union, though naturally they put a more inspiring spin on the EU. Europeans have, in this narrative, rejected extremist ideologies in favour of a calmer, more pragmatic world that embraces the realities of capitalism and liberal democracy.

Still, inspiring or not, there isn’t anything particularly controversial there, one would think, except for the very partisan model envisaged by the organizers, who are bent on equating 20th century communism with fascism, while counterposing the various pro-capitalist shades as the true bearer of European civilisation in contradistinction to the totalitarian ideologies of the 1930s.

Sigfrido made the case for historians of the left to participate in the project so as to not allow that narrative go uncontested. For the project for a united Europe is also, of course, a project of the left, which, apart from the Labour Internationals themselves, saw numerous figures from Bakunin(!) to Lenin calling for a United States of Europe long before the German High Command was seduced by its dreams for a Mitteleuropa, let alone before the peculiarly distrustful technocrats like Monet and Schuman got their chance after the mess the nation states had made during the Second World War.

But why should leftists bother with the narrative of the Communists as a force for evil? The Berlin Wall has been torn down; the Soviet Union is but a fading memory in some babushka’s mind. Our latter day Bolsheviks are hardly about to storm the Commission’s headquarters and put the stagaires up against the wall.

So why not dispense with the Communist legacy and start the project for a free and fair society with a slate unbesmirched by the Purges or the suppression of the Prague Spring? This, certainly, is an attitude widespread in new movements like the Occupy phenomenon of 2011 while even actual socialists often take a position none too far from it in practice: witness the SWP’s resolute identification of the USSR as state-capitalist remains a source of pride for many of its supporters.

Well, the right-wing in Europe clearly take a less nonchalant view of the Communists. Many of these efforts gain their fury from the right-wing of countries in Eastern Europe, who are no doubt attempting to construct a narrative of national resistance to Ronald Reagan’s Evil Empire. But they receive substantial support from allied forces in the west, as is evident from the House of European History itself.

The purpose of the House of European History, beyond the nondescript and unobjectionable platitudes of engendering awareness of our past, is to construct a narrative that severs the population from any lingering loyalty to the idea of a socialist movement as the spearhead of human liberation. Or, to put it another way, the effect is to cast capitalist democracy as the exclusive embodiment of progress while identifying the socialist and communist movements with Nazism in a catch all category of Very-Bad-Things called ‘totalitarianism’.

For the campaign to treat Nazism and Communism as two poles of anti-human philosophies is not an isolated occurrence; it merely constitutes the institutionalization of a wider pattern. Already the European Union commemorates the certainly shameful Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The exigencies of realpolitik — not least the purchase of strategic depth that probably saved Europe from decades of Nazi rule — may ultimately be no excuse for the Communist compromise but given the refusal of the western allies to make a pact with the Soviets in 1939 and their near insatiable desire to do deals with Hitler (e.g. Munich, the Anglo-German Naval Treaty, the militarization of the Rhineland), it takes a breathtaking level of hypocrisy to make the pact into a major event, rather than the temporary truce it so clearly was.

The identification of the Soviets as little better than their Nazi opponents also entails not a little absurdity given petty details such as the continuing existence of the populations of Eastern Europe even after a half-century of Soviet dominance, which, after all, compares well to the fate of the peasants of Central America in the 1980s, let alone to Eastern Europeans’ own fate during the relatively brief Nazi occupation of the 1940s. Over 13 million civilians died in the USSR alone. And this leaves to one side the fate of the Eastern European population if General Plan Ost had been successfully carried off as intended.

In General Plan Ost, Hitler aimed to emulate the United States’ continental expansion through the conquest and clearing of Eastern Europe

Moreover, it takes some chutzpah to write that the liberation of Europe from the Nazis began in 1944, as the project for the House of European History does, in effect denying that it was the Soviet Union that defeated Germany; that the counterstrike of December 5th outside Moscow prevented an early Nazi victory, that the epic Battle of Stalingrad signaled the decisive turning of the tide in the European theatre. And of course, that outside the Soviet Union, it was the Communist led partisans that ground down the Nazis; in the case of Yugoslavia right down to their eventual defeat; in Italy and France to the extent that they were acknowledged as the most cohesive anti-Nazi resistance.

Since every transition to industrial society was characterised by a widespread social upheaval — from the shunting of the peasantry into the dark satanic mills of 18th century England to the massive factories of present day China — the cruelty of this process cannot be completely airbrushed from the history of capitalist societies any more than it can for the USSR.

The widespread trauma of the transition to capitalism makes it more pressing, in particular for the western democracies, to separate the immediate response of popular organisations, namely the formation of trade unions as well as movements for limited social reform, from the grander projects that sought to replace capitalism itself. The working class movement has always contained a number of strands, from those seeking the amelioration of capitalism to its overthrow. However, it was the labour movement’s organic alliance with an explicitly socialist project, one which lasted for much of the late 19th and 20 centuries, that provided the ideological backdrop necessary for it to assume the scale of a global project aimed at superseding capitalist production itself.

Although the purely trade unionist tendencies, which were content to make their peace with class society, usually emerged as the dominant force, the history of the continent makes very little sense if ‘gas and water’ socialism is treated as the alpha and omega of the left. We would, in effect, be reduced to a Hollywood good guy/bad guy narrative in which nefarious Marxists intrude upon the natural role of labour by leading the ignorant workers astray, before destroying themselves through their very successes. Simplistic as the good guy / bad guy narrative may seem, it’s a tactic that plays surprisingly well with even progressive intellectuals.

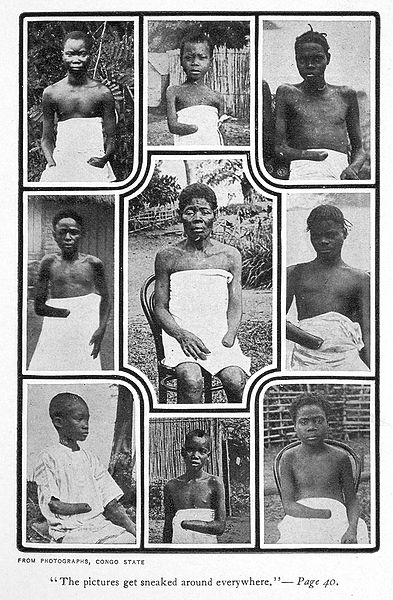

The Communists operate under a particularly insidious rulebook: if a famine occurred under a communist regime, it is the responsibility of Marxist ideology: hence The Black Book of Communism. But if comparable famines or even a slow-motion genocide, such as hit the Native Americans, occurs under the aegis of a capitalist state it is merely a mistake or, at most, the partial responsibility of that particular government for which a begrudging apology can be issued a century or two down the line. Certainly there are few people, even in Ireland, who attribute the Great Famine to capitalism, even though it clearly swept away the then dominant form of pre-capitalist production. Such thoughts are seldom formulated and even less articulated even by historians on the left of the political spectrum.

Wikipedia: Congolese children and wives whose fathers failed to meet rubber collection quotas set by Belgian capitalists were often punished by having their hands cut off.

Of course, the Socialist movement, in all its guises, has many black deeds to its name. But that is not the end of the matter, for the source of these deeds is not so simple, nor their actuality even decisive. The Stalin regime cracked under the pressure of a failing, encircled revolution and resorted to patently unjust and counter-productive measures. As Magri argued, Socialists certainly have to face up to unpleasant realities. But facing up is not the same as giving in. As reprehensible as, say, the Great Purges undoubtedly were — and they were the single worst atrocity attributable to the left in 20th Century Europe — they arose in spite, and not because of, the goals and intentions of the Communists. For the socialist objectives of universal equality, liberty, and solidarity are in such total contrast to the utterly miserable philosophy of the Hiterlites — racial struggle and the subordination, even extinction, of allegedly biological different peoples — that it requires an intense level of indoctrination to fit them into the same category of ‘totalitarian’.

One has to understand the movement in its entirety and if the Left, like all political tendencies, has its share of crimes to atone for, it also its many positive aspects. In this it is no different to the Catholic Church or liberals or nationalists whose movements are full of contradictory actions. Nor is the reduction of the Communist movement to the worst decade of Stalin’s rule an accurate reflection on the immensity of the contribution of European communists, let alone the socialist project as a whole, to human liberty. Millions of men and women expended countless hours working for a co-operative world and, leaving aside the anti-colonial movements that adopted the rubric of communism, built up long-lasting institutions in many western countries that contributed significantly to the welfare of these societies.

The attempt to smear Communism with the label totalitarian arises not from legitimate criticism of its many, many mistakes but from a desire to demonize, even criminalize, the project to create a co-operative world beyond capitalism. If even the very attempt to collectively run society is doomed to end in totalitarian excess, then socialism in any form is finished and its tradition is not something from which modern radicals can build. The only ethical options open to radicals is a toothless human rights activism.

The great movements of history have plenty of less than stellar deeds to their name. Do Catholics renounce Rome because of the Inquisition? Do liberals decry capitalism because of the Irish and Indian famines? A purely moralistic rejection of the Communist tradition, along the lines of House of European History project, is essentially institutionalized superstition and, consequently, utterly unilluminating except as to the fears of its backers.

It might be retorted that comparing the socialist movement to the institutions of the old religions merely confirms the bankruptcy of both and that either a wholly new ideology or none at all is what is required at this juncture.

But no ideology will be able to come to dominance without encountering a very messy reality which necessarily entails very messy compromises and, quite simply, making a lot of mistakes, some of which are strategically disastrous. And the rejection of all ideology offers no relief, let alone a panacea, to those seeking an alternative to capitalism, for without some grand narrative that gives meaning to the effort to organise collectively, there can be no coherent organizations at all. The function of ideology is to cohere the organizers, without whom there is simply an amorphous and easily contained mass. Since transformation of the social structure is not possible without such organisers, we are, so long as we are without an ideology, truly at the end of the history.

Which, as it happens, is none too far from where the purveyors of the identity of fascism and communism leaves us. The stakes, then, are higher than the good name of militants past. To sever the link with the great working class movements of the last two centuries is to disorganise the possibility of a modern movement for a co-operative alternative to capitalism. The removal of socialism from the menu of movements striving for human emancipation is fundamentally a blocking move in an era of capitalist bankruptcy. The current and ongoing spectacular failure of capitalism to provide the framework for that emancipation necessarily results in socialism being a viable contender.

If capitalism succeeds, as it nearly has, in ridding the population of its antiquated and peasant based superstitions, and of developing highly advanced levels of productivity what prevents us from progressing on towards a society based entirely on a co-operative economy, that is, socialism? The answer is a lack of socialist organisations and it follows that the ruling class have a structural interest in taking steps to prevent workers from making any moves that can develop mass organizations with a socialist programme.

The struggle for history therefore matters because it isn’t just a question of history but a question for the present. On which side of the barricades will the new generations fall? Will they compliantly direct their idealistic energies towards reproducing capitalism, albeit tinged with a missionary zeal for human rights or perhaps an inchoate rage against the 1%? Or will they, like their ancestors, be more ambitious and attempt to take the achievements of the socialists of the past as their starting point and build comparable institutions that can conceivably pose a threat to capital?

The question becomes all the more pressing as the options for the development of a society based on a capitalist mode of production become more limited over the next half-century, as automation encroaches on the domain of services, as the rural reserve of labour is finally exhausted and the geo-political dash for supremacy enters a more unpredictable era, all in the midst of world coming under increasing ecological pressure.