This introduction and interview is from “On Our Knees: Ireland 1972” by Rosita Sweetman

This introduction and interview is from “On Our Knees: Ireland 1972” by Rosita Sweetman

Introduction

The Irish Republican Army officially came into being when Padraic Pearse read the Proclamation of Irish Independence from the steps of the General Post Office in Dublin on Easter morning, 1916. The IRA traces its roots right back through all the physical force resistance groups that at various times throughout 700 years of British domination of Ireland had risen up to try and get them out. Its recognised father figure is Theobald Wolfe Tone, of the United Irishmen, and his grave is the scene of an annual re-affirmation of Republicanism.

The IRA was the army of the people during the War of Independence (1919-1921). They secured military victory for the Irish people in that they forced the British to the conference table, but were sold down the Swanee by political leaders who divided on the Treaty offered by Britain. The compromise reached was that Republicans would have a 26 Country “Free State” to run as they wished in theory (in practice of course it was to be run as the British wished as they still held the purse strings), and the 6 remaining counties were to be jointly controlled by the Unionists in Stormont, and Westminster. In the absence of the British enemy the Irish turned on each other and the resulting Civil War saw the IRA defeated, the Free Staters in control and building bourgeois Ireland under President Cosgrave. Thousands of IRA men were imprisoned and interned and Ireland settled down temporarily to trying to become a nation of grocers and big farmers.

In 1927, Eamonn De Valera, a veteran of the 1916 rebellion and leader of the anti-Free Staters, decided that the cold of remaining outside the Free State parliament hitherto unrecognised and boycotted by Republicans (or anti-Treaties), was too cold. By 1932 Dev’s new party, Fianna Fail, was able to secure 72 seats in the General Election, and completing a political Houdini on the Oath of Supremacy to the British Crown, Dev led his new Party into the Dail. The Republican Movement was split down the middle. Some felt Dev was right to enter the political arena and beat the Free Staters at their own game, others believed that compromise would eventually result in a watered down Free State, and more importantly a continued recognition of the Border which separated the Six Counties from the rest of Ireland.

Dev did release Republicans imprisoned by the Free State government, started the Economic War with Britain by refusing to continue paying land annuities to that country, but hopes that Fianna Fail would be the political expression of the ideals of the IRA were soon shattered. The following four years saw Dev consolidating his parliamentary position; the dropping of Sean MacBride as the radical Chief of Staff of the IRA; the appointment of a far more conservative Chief of Staff, Tom Barry; boredom amongst IRA volunteers in the absence of any military action, and 80 of them leaving for Spain to fight alongside Republicans there.

By 1939 the full betrayal on Fianna Fail’s part of Republican principles became startlingly clear to all when the IRA launched a bombing campaign in Britain, designed to show the British and Irish governments that not all Irishmen were happy with the puppet “Republic”. Dev’s answer to his old comrades in arms was the opening of internment camps in Curragh, and military courts which gave widespread powers of arrest and detention of Republican “suspects”.

The IRA staggered on through the forties. A planned campaign against the Northern Ireland state was dropped. Cathal Goulding, a young IRA volunteer, was elected to a provisional Army Council, a few months later all members of the new Council were arrested. In the middle of the forties Sean MacBride, formed “Clann na Poblachta” – designed to be the expression – again – of republican principles inside the regime.

By the late forties the battered remnants of the IRA called a convention at which military campaigns against Britain and Northern Ireland were planned, as well as aggressive military action in the South. IRA volunteers were forbidden to join the Communist Party, and were told summary dismissal faced them if they appeared in court on even the smallest charge. The IRA was to be untarnished by either “the red peril” or shades Chicago gangsterism. The same year Sean MacBride’s new party won ten seats in a General Election, and formed a coalition with the old Free State party, now called Fine Gael. Costello, as Taoiseach, proclaimed the Republic of Ireland. Britain’s answer being the Government of Ireland Act which formally handed over control of the North to the Stormont regime.

The middle fifties saw the IRA’s Border Campaign against Northern Ireland beginning. It was called off in 1962. Militarily and every other way the campaign was a complete flop. The Catholics in the North were on the whole disinterested in the IRA plan. Internment was introduced North and South and thousands of IRA men picked up.

In 1962, Cathal Goulding, just out from internment, and prior to that having served an eight year sentence in Britain, was elected Chief of Staff of the depleted and woe-begone Army. He ordered a complete moratorium (sic) of Republicanism since 1798, on the whole physical force tradition in Ireland, and on why, if so many Irishmen were prepared to die for Ireland, they never succeeded in freeing her.

The sixties was a period of re-assessment for the Republican Movement. Those anxious to get back on the border with guns and bombs were told to wait. Marxist intellectuals like Roy Johnston were co-opted on to a kind of “Think Tanks” to draft policies for discussion. By 1964 a nine point document was presented to an extraordinary Army Convention. Suspicions that the Army had “gone soft” were confirmed in the eyes of the old style IRA men, those who felt that the problem in Ireland consisted of the Border and nothing else, and that problem could only be solved by physical force. The new policy of the IRA was based on Marxist ideology. That if political power comes out of the barrel of a gun it’s necessary to gather the political ammunition of the people before firing the gun. Recommendations to the convention included the dropping of the “abstention ban” on Sinn Fein representatives (Sinn Fein being the political wing of the IRA) taking up their seats in the Dail or Stormont; the formation of a popular or national front with other left-wing movements; the engagement of members of the movement in all types of agitationary movements, whether through members of existing pressure groups, or the formation of new ones. If the IRA was really to be “the army of the people” as it claimed, then, it was argued, it must first identify with the people and their everyday struggle for existence.

Advising men whose expression of Republicanism had hitherto been midnight raids on the Northern border to take their place in the picket line alongside Socialists and Communists was not going to be an easy task. Ireland is a deeply conservative country and the Republican Movement as a whole reflected that conservatism. The Republican Movement had been following the holy grail of a “United Ireland” for too long, and at any cost, with the gun, to easily switch to political education and working with the people. De Valera’s accession to power had confused many Republicans, who still thought along Civil War lines, and thought all problems lay North of the border. Awakening them to the fact that bourgeois capitalism, or “green capitalism” existed in the South, that Fianna Fail were just as efficient lackeys of British business interests as the Unionists in the North, just as efficient expressions of the “cois muintir” (working class) was going to prove a long haul.

Some evidence of the threat the new Marxism of the Republican Movement posed to the Irish state, though, can be seen in the events which led up to the split in the Movement in January 1970. Through 1969 paid agents of the Fianna Fail government were told to infiltrate the IRA to reactivate the old physical force elements still living in romantic nationalistic dreams. A renewal of sectarian strife in Northern Ireland in August 1969 ensured that at least some of the old IRA men accepted the money and the arms offered by these agents of the Fianna Fail government in return for breaking away from Dublin Headquarters and its Marxist doctrines and pledging to concentrate activities in the North through the physical force method.

The crisis of August ’69 produced the denouement needed by the establishments North and South. In the North it ensured that the inching progress being made towards smashing sectarian barriers between Catholic and Protestant and the gradual democratisation of the State was halted. In the South it produced the necessary catalyst to call out all the latent nationalism in the people there which blinded them as to their oppression by Fianna Fail and ensured Fianna Fail’s continuance in power as long as the Provisional IRA maintained a physical force campaign.

The intensification of the Provisionals’ military campaign throughout ’71/’72 was, in the words of one Republican, “with the dust of the fucking bombs flying nobody could see where we were going.” Internment succeeded in halting the burgeoning political education programme of the Official IRA, further polarised the two communities as Catholics resisted it with vehemence and violence increased.

With the temporary suspension of Stormont the Provisional IRA went into decline. What they’d been demanding all along was suddenly granted overnight and their lack of political education, even of their own members, let alone the people on whose behalf they professed to be fighting, produced a crisis within the Movement. The Officials see the suspension of Stormont as another “mystification” of the essential problem – British imperialism.

In the short term the Officials believed that one of the basic problems in Northern Ireland was the division of the working class; that this division was no longer useful to Westminster, that therefore some sort of compromise government, or commission, must be established to govern Northern Ireland in Britain’s interest but with less blatant sectarian overtones than the Unionist Party.

While the Provisional IRA sees a United Ireland as one of its most important aims, the Officials feel that a United Ireland could be worked out within the next couple of years, initially through a federal solution linking Dublin, Westminster and Belfast. A United Ireland the Officials believe would confuse many “nationally minded” people who would see the problem as at last being solved.

The problem can only be solved, they say, when the grip Britain has over Ireland, by extension the grip the lackeys of British Imperialism have over Ireland – Fianna Fail and their cohorts – and the Unionists in the North – are all broken, and a socialist republic set up. They have no doubt in their minds that this is a long hard struggle.

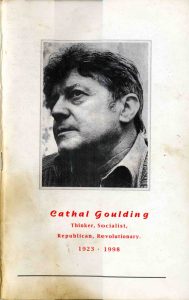

Cathal Goulding

STATEMENT TAKEN DOWN, EARLY 1972, VINDICATING SOCIALIST-REPUBLICAN POLICIES OF OFFICIAL IRA IN THE SOUTH AND NORTHERN PARTS OF IRELAND:

“I think from the time I first really started to think about revolution I felt the Republican Movement was the right one for Ireland. It was the people’s instinctive reaction to British Imperialism and through it I felt they would accept Socialist ideas that they mightn’t say accept from something like the Communist Party.

“In 1962, I was elected Chief of Staff of the IRA. The Northern Border Campaign had just been called off. At that stage I felt what we needed to do in the Republican Movement was to sit down and have a good look at the whole revolutionary movement in Ireland – from 1798 up to today, I and others, felt that the Movement as a whole had never given a thought to winning a war. They only thought of starting one. What we lacked was the support of the people. The reason we didn’t have their support was that the people didn’t understand what we meant by freedom. They thought it was a sort of Brian O’Higgins type glorious vindication of the Irish race. This wasn’t our idea at all.

“Our struggle must be a socio/political one. Something to do with the ordinary people. The middle class Irish felt as emancipated as they ever would be, the people who needed the freedom were the people who had nothing. This is what we were fighting for, and we had to make it plain to the people. To do this we had to involve ourselves in their everyday struggles for existence. In housing, land, trade unions, unemployment – maybe it would take ten years of working like this before we could even say we had the basis of a revolutionary movement.

“A meeting of the IRA Army Council was called, and the Army Executive. We set up a committee to study the Movement. Most people felt we should re-organised the fighting units, get more arms and money and start the war all over again. It was pointed out that this had been done before and always ended up as it did in 1962 – the Movement practically smashed.

“In 1964 a nine point document was presented to an extraordinary Army Convention. It was for internal use only and dealt with what we should do as a revolutionary force. The main recommendations were dropping of the abstention ban on participation in parliament and the formation of a national liberation front to unite all the forces fighting against the Establishment. The job of the guerrilla fighter is to fight, or not to fight, according to the tactics that suit him best. There should be no hard and fast rules.

“As far as success goes I think its too early to think of success. We did help in initiating a very good housing action group in Dublin. We’ve been very active with the people in land agitations, in the protection of Irish fisherman, in the fight for the ownership of Irish rivers. The reciprocal support has been small. I don’t think this is the fault of the people, it’s partly that our movement wasn’t geared to this type of action at the time. Most of the people in the Movement were geared to a physical force campaign. First of all political agitation wasn’t as exciting I suppose.

“When we set about initiation our agitation movement in the North we came up against a blank wall. We were amateurs in a sense, and the Republican Movement was completely outlawed in the Six Counties. Before we could get any kind of proper agitation moving we wanted to clear the ground for political action. In other words to gain freedom for political manoeuvrability. The first thing we needed was civil rights. There was a kind of Mickey Mouse movement which wrote letters to the Government about prisoners in South Africa or something, so we decided to revive that. We told Republicans to join the Civil Rights Movement and to develop it, with the idea of gaining civil rights in the North.

“As long as the Civil Rights Movement didn’t look for revolution, or total freedom or unification with the 26 Counties, then we felt this would help get the Protestants involved, and get away from the old divisions. Our objectives were civil rights reform, for Catholic and Protestant working class, and the splitting of the Unionist Party.

“The Civil Rights Movement went from strength to strength. There were a lot of Protestants high up in the Six Counties at the time who were hankering after respectability. They wanted a democratic state like Britain. The people in power, the Unionists, knowing if the Movement did succeed it was the end of Unionism manufactured artificial pogroms on the Catholics to bring up the old enmity between Catholic and Protestant. This is now an established fact. The RUC and the B Specials led the Protestants into the Bogside in ’69 burning the houses and shooting people; the so called pogroms in Belfast were also led by the RUC and the B Specials.

“The pogroms of 1969 against the Catholic population produced the Provisional IRA. They in turn are now creating the necessary Protestant backlash, while the Establishment is still trying to ensure that there is no spread of civil rights demands into the Protestant working class.

“In 1969 certain agents and members of the Fianna Fail party were sent to infiltrate the IRA. When they found they couldn’t get any change from us they started working on the men in the North. The members there were told if they broke away from what they (the Fianna Fail agents) called the Marxist/Communist group in Dublin they’d be given arms and money. We were told in the South by these same men to stop attacking the establishment in the 26 Counties, drop all socialist policies and have an all-out attack on the Unionists in the North. What they wanted in fact was a development of Fianna Fail power into the Six Counties through a sectarian war. I told these agents we would decide how the arms and money would be used if we did decide to take them – and then all discussion stopped. We did in fact get money from Fianna Fail people collecting in London – I’ll take money from President Nixon if he offers it, but I’ll spend it the way I want.

“In January 1970 the Republican Movement split. I think it was inevitable. In Ireland you’ve always had this left/right struggle. The provisionals didn’t like our socialist policies. They saw the abolition of Stormont as a primary aim. We see Direct Rule as a retrograde step. You simply have a number of Commissioners regulating the Civil Service and the police. They’ll be the same Civil Service and the same RUC.

“What we want is democratisation of the system in Northern Ireland – more democracy, not less. We want the representatives of the people, to be the civil rights workers and people like Paisley and Boal. This means that the old political power blocs will be broken down. They are breaking down already. With civil rights guaranteed by some Bill of Rights the present regime couldn’t continue – you can’t have a dictatorship administering a democracy. Our aim is to develop the political and passive resistance of the people to the point where the administration just can’t administrate any more.

“I’m a physical force revolutionary. I’m not naive enough to think that we don’t have to use guns. An armed proletariat is the only assurance that they can have the rule of the proletariat.

“But we believe that the most important thing in the Six Counties at the moment is the civil resistance campaign. We have used every effort to try and get the people back on the streets, the demonstrations, non-payment of rent and rates, passive resistance. This is the most important phase of the struggle because it involves the people. You might have 500 armed IRA men in the North but it wouldn’t be as good as 10,000 people resisting in a passive way. The two together would be even better of course! but the most important part of any revolution is the involvement of the people, this ensures that when a settlement comes the people will have to be represented at the talks.

“In 1969-70 you had the Citizens Defence Committees in the different areas – Protestant and Catholic. This was a revolutionary development. Irrespective of the people’s reasons for it. Once they begin thinking along independent lines you slowly break down the power the political parties have over them. There was joint action on a number of occasions between Protestant and Catholic working class. The Protestants wouldn’t be in favour of the IRA, but it was a contact, for a certain limited social objectives – bettering housing, better jobs.

“Due to the sectarian bombing and shooting campaign of the Provisionals this has now broken down. The non-payment of rents could have drawn in the Protestants if it hadn’t been for the Provo’s campaign. If a Protestant worker, working alongside a Catholic, knew that the Catholic was drinking his ten bob rent instead of paying it to the Local Authority, he’d very soon say to the Authority, ‘Well if them Fenian bastards aren’t going to pay their rent, I’m not going to pay me fuckin’ rent either’.

“The main function of the Official IRA in the North at the moment is to see that there is a mass involvement. That the street committees and all kinds of civil resistance committees become kind of People’s Soviets, actually administrating the areas. We would like to see the local IRA units putting themselves at the disposal then of these committees for the defence of the areas, to be the armed cadre of the people. In the case of the IRA administering law and order I don’t think this should be done. I think the people should administer their own law and order and if they want the IRA’s help they could call on them. In the end we won’t have to go out and attack the British Army, but the British Army will have to come in and attack the people in these areas who are opposing the Establishment. They’d have to come in and put a soldier on every doorstep.

“If the people are in control of their own areas they can have a say in any settlement that comes. Even if they’re from the Shankill Defence Association and are bigoted initially, in the final analysis theyll be forced by their own people to represent local interests. It the Catholics then are demanding better houses and better jobs, the Protestants won’t sit around simply demanding a defence of the Constitution – they’ll want the same social demands as the Catholics. Any advance the Catholics make towards civil rights, as workers, the Protestants will want the same. This will bring them both into confrontation with the Establishment, the more this happens the more you will break down the traditional loyalties and power blocs.

“We could produce a crisis situation in the morning in the North, either with the Provos on our own. But what would happen? Would the British say ‘okay, here’s the Six Counties, have your little workers republic’, or would they say, ‘we’re getting out altogether’? I don’t believe they’d say either. What they might do is have some kind of federal solution, or a united Ireland, with the 26 Counties re-enforced to protect the interests of Capitalism, British Capitalism. A United Ireland would confuse a lot of ‘nationally minded’ people in Ireland. They would support it, and this would mean a lessening of support for revolutionary forces. I don’t see any difference between Jack Lynch and Brian Faulkner. I’m sure they could hammer out some solution – but what would that bring? Simply a re-enforcement of the grip that vested interests have in Ireland.

“Political power vested in the people through the street committees, will slowly but surely develop the take over of industrial resources, and the means of production, distribution and exchange in the Six Counties, which will have an effect on the 26 Counties as well, democratising it, and this would allow us to develop towards a 32 County Workers’ Republic.

“At the moment though we consider the anti-EEC campaign to be the most important issue in the country, North and South. If the EEC becomes a fact then the establishment of a socialist Republic in Ireland is going to be put back for maybe hundreds of years. The EEC bloc is one that has been developed by the big cartles of Europe and America, it’s anti-social. Ireland would become a hunting, hooring, and fishing group for the big business elements in Europe.

“In the North we believe we must continue to critise the actions of the Provos because basically they are anti-people. In the sense that onece they alienate any one section of the Irish working class community they are wrong. A Workers’ Republic isn’t possible without the co-ooperation of a fairly large section of the Protestant working class community. Our aims on this line would be to bring in or neutralise, in some shape or form the working class Protestants into the struggle.

“I believe in the long run we’re in a better position organisationally than the Provos. They’ve lost a lot of their Northern leadership through people like Joe Cahill, Martin Meehan and those having to come to the South. The Provos are now coming back to the situation where they can’t mount a decent military operation with the Six Counties, but have to attack over the border from the 26 Counties. As their military leadership begins to decline so will their military activities. What helps the Provos most in the North is that every Catholic youth is a Provo at heart. They can be used individually by the Provisionals for one operation, say planting gelignite in a shop. In this way the campaign can go on for a long time. Anyone who kills a British soldier is “a good fuckin’ man’ in the Catholics’ eyes. They may be more popular too in a military sense, people say – “well they’ve shot more of the bastards than you lot have”, or, “you people are not half as good in an aggressive sort of way as the Provos”. But when it comes down to the cold logic, to a committee of people deciding what they want done, and how they can get it, I think they will trust us far more. We want all our units answerable to these local committees – in the end I think the majority of people will see the difference between the pay-off of violence, and the pay-off of the civil resistance campaign.

“The basic difference between us and the Provos is that they believe that by uniting the Catholics North and South they can have a United Ireland, we say you can’t. The middle class Catholics in the North are just as worried about retaining their stranglehold over the people as the middle class Protestants are. They’d all love some kind of settlement so they can get back to the business of making money.

“I think the role of the IRA in the North now is to get back to a situation where we can organise in a revolutionary way. I think while the ‘no go’ areas in Derry provide an opportunity for developing revolutionary consciousness among the Catholic working class, they [the barricades] are creating a greater barrier than the old barriers of State sectarianism to our getting across to the Protestant working class.

“I think some form of peace should be established. I don’t mean the peace that will allow the establishment to continue its exploitation of the people, or the peace that will allow them to hunt down men on the run, but peace on our terms.

“These are: (1) an end to all repressive laws (such as the Special Powers Act.) (2) The unconditional release of all internees, an amnesty for men on the run and release of political prisoners. (3) The withdrawal of the British Army to their barracks, pending their complete withdrawal from Northern Ireland. (4) A declaration of intent from the British Government that we in the Republican Movement will have the freedom to operate openly like any other political organisation.”